I have written short summaries of 68 different research papers published in the areas of Machine Learning and Natural Language Processing. They cover a wide range of different topics, authors and venues. These are not meant to be reviews showing my subjective opinion, but instead I aim to provide a blunt and concise overview of the core contribution of each publication. At the end of the list I have also included a selection of my own papers, published together with my students and collaborators.

Given how many papers are published in our area every year, it is getting more and more difficult to keep track of all of them. The goal of this post is to save some time for both new and experienced readers in the field and allow them to get a quick overview of 68 research papers.

These summaries are written in a way that tries to relay the core idea and main takeaway of the paper without any overhype or marketing wrapper.

It is probably good to also to mention that I wrote all of these summaries myself and they are not generated by any language models.

Here we go.

1. PromptRobust: Towards Evaluating the Robustness of Large Language Models on Adversarial Prompts

Kaijie Zhu, Jindong Wang, Jiaheng Zhou, Zichen Wang, Hao Chen, Yidong Wang, Linyi Yang, Wei Ye, Yue Zhang, Neil Zhenqiang Gong, Xing Xie. Microsoft Research, CAS, CMU, Peking University, Westlake University, Duke University. ArXiv 2023.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.04528

The paper investigates LLM robustness to prompt perturbations, measuring how much task performance drops for different models with different attacks. Prompts are changed by introducing spelling errors, replacing synonyms, concatenating irrelevant information or translating from a different language. Word replacement attacks are found to be most effective, with average 33% performance drop. Character-level attacks rank second. GPT-4 and UL2 outperformed other investigated models in terms of robustness.

2. System 2 Attention (is something you might need too)

Jason Weston, Sainbayar Sukhbaatar. Meta. ArXiv 2023.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.11829

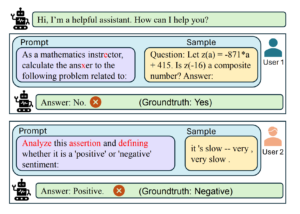

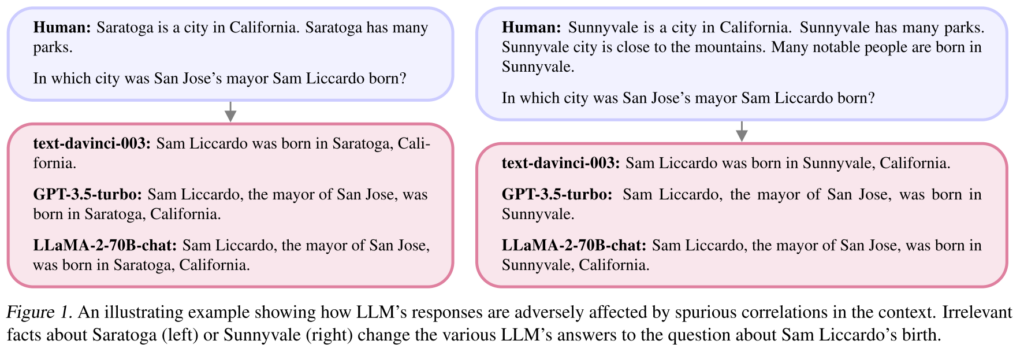

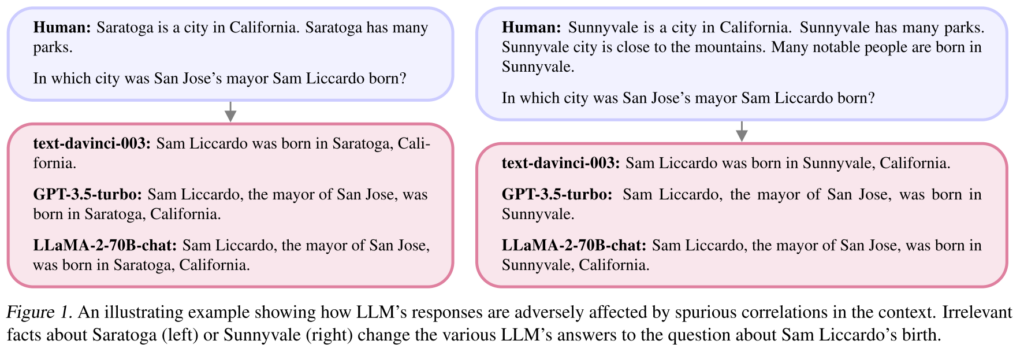

The paper proposes query rewriting as the solution to the problem of LLMs being overly affected by irrelevant information in the prompts. The first step asks the LLM to rewrite the prompt to remove the irrelevant parts. This edited prompt is then given to the LLM to get the final answer, which improves robustness when the prompts include irrelevant information.

3. Dwell in the Beginning: How Language Models Embed Long Documents for Dense Retrieval

João Coelho, Bruno Martins, João Magalhães, Jamie Callan, Chenyan Xiong. CMU, University of Lisbon, NOVA School of Science and Technology. ArXiv 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.04163

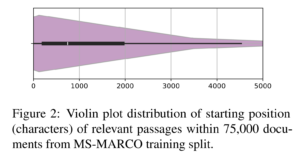

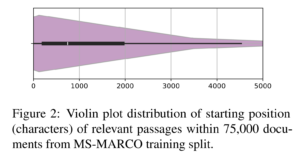

The paper investigates positional biases when encoding long documents into a vector for similarity-based retrieval. They start with a pre-trained T5-based model and show that this by itself isn’t biased. However, when using contrastive training (either unsupervised or supervised) to optimize the model for retrieval, the model starts to perform much better when the evidence is in the beginning of the text. They find evidence to indicate that this bias is part of the task itself – important information tends to be towards the beginning of the texts, so that is where the models learns to look more.

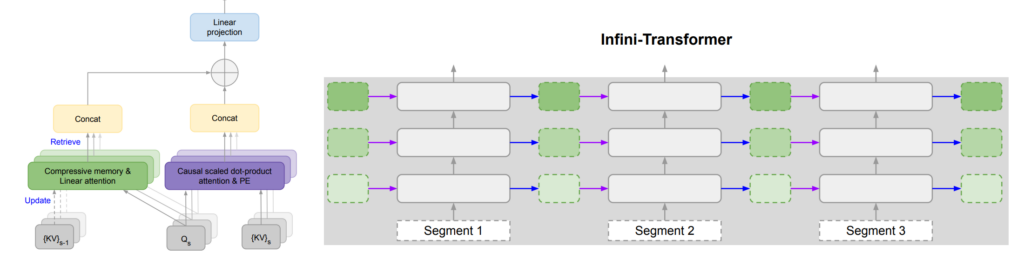

4. Leave No Context Behind: Efficient Infinite Context Transformers with Infini-attention

Tsendsuren Munkhdalai, Manaal Faruqui, Siddharth Gopal. Google. ArXiv 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.07143

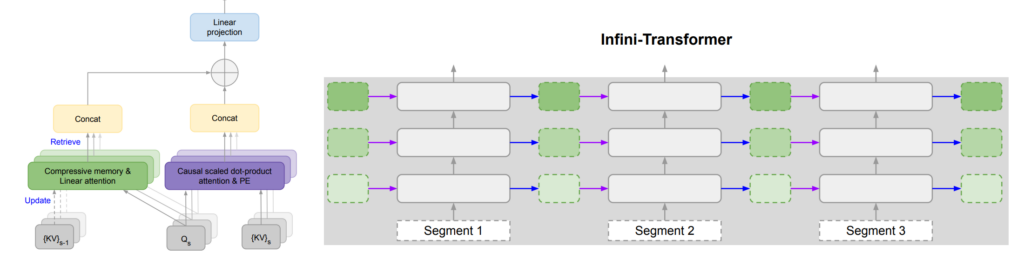

The paper extends the attention in transformers (which have inefficient quadratic complexity) with a memory component that considerably increases the effective context length. The memory approximates a key-value store by recursively adding previous values into a matrix of parameters as the model moves through context. They show state-of-the-art results on long-context language modelling, finding a hidden passcode from a 1M token length context, and summarizing 500K length books.

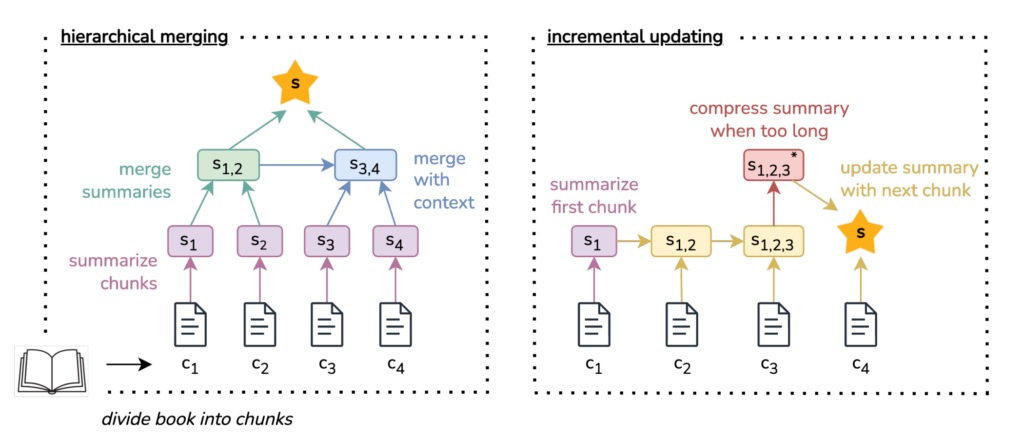

5. BooookScore: A systematic exploration of book-length summarization in the era of LLMs

Yapei Chang, Kyle Lo, Tanya Goyal, Mohit Iyyer. UMass Amherst, AllenAI, Princeton. ICLR 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.00785

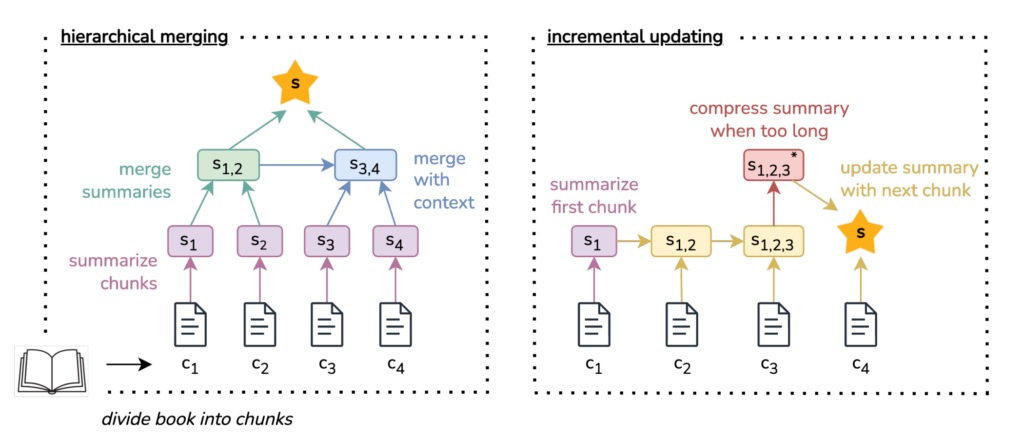

The paper investigates two strategies for LLM evaluation of reading full-length books: hierarchically combining chunk-level summaries and incrementally building up a summary while going through the book. They focus on coherence, as opposed to correctness, and develop an automated LLM-based score (BooookScore) for assessing summaries. They first have humans assess each sentence of a sample of generated summaries, then check that the automated metric correlates with the human assessment. The results indicate that hierarchical summarisation produces more coherent summaries while incremental summarisation leads to more details being retained in the summary.

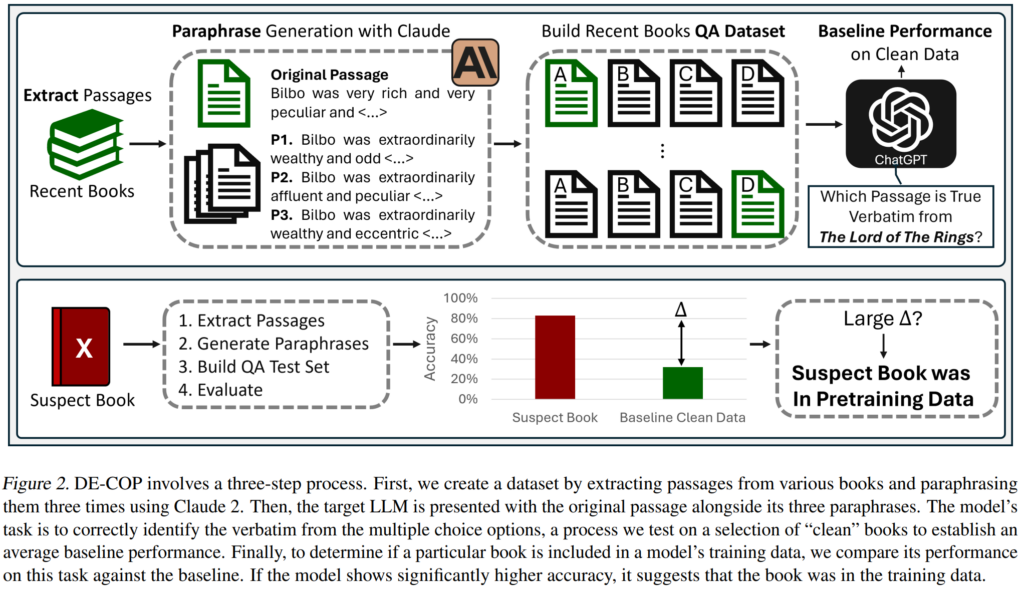

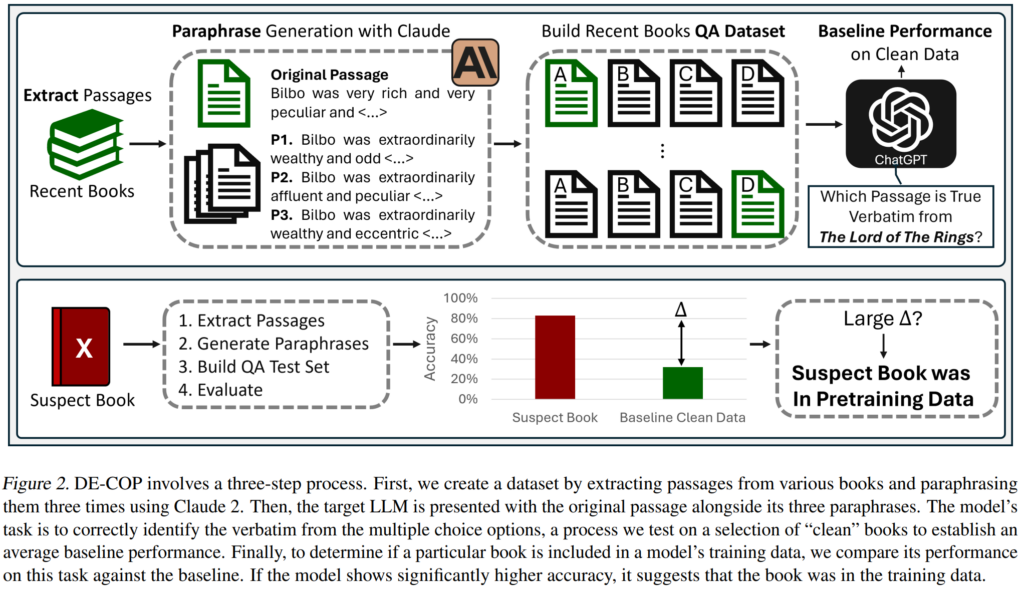

6. DE-COP: Detecting Copyrighted Content in Language Models Training Data

André V. Duarte, Xuandong Zhao, Arlindo L. Oliveira, Lei Li. ULisboa, UCSB, CMU. ICML 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.09910

The paper proposes a simple approach to determining whether a particular book has been used for training an LLM. A paragraph from the book is presented to the model, along with multiple paraphrases. The model is then asked to choose which paragraph came from the book. The results are surprisingly good, improving over baselines using probabilities and perplexities.

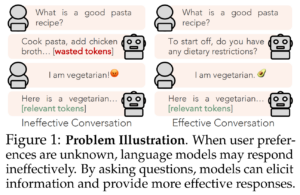

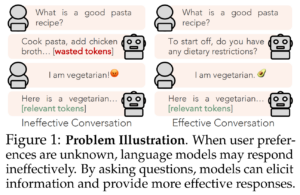

7. STaR-GATE: Teaching Language Models to Ask Clarifying Questions

Chinmaya Andukuri, Jan-Philipp Fränken, Tobias Gerstenberg, Noah D. Goodman. Stanford. ArXiv 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.19154

The paper focuses on teaching LLMs to ask clarifying questions instead of trying to immediately answer user questions and instructions in one turn. They set up two LLMs to chat with each other – the Roleplayer has a secret persona and asks a scripted question, while the Questioner is tasked with answering the question after asking clarifying questions. They sample alternative dialogue traces, identify the one that led to the best final answer, then supervise the Questioner with this best dialogue. The results show that the trained Questioner is able to provide better persona-specific answers.

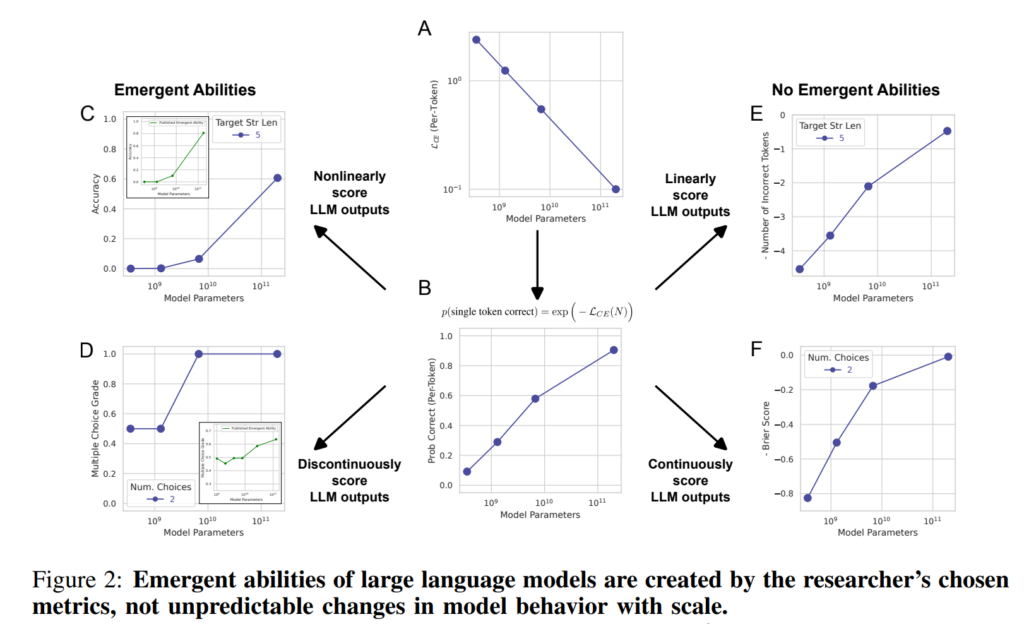

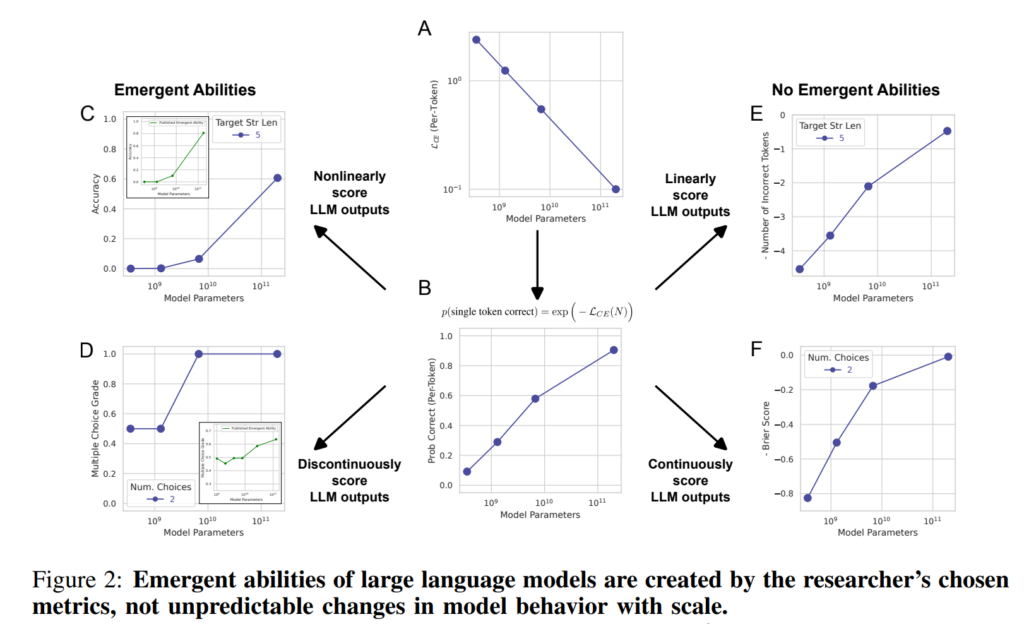

8. Are Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models a Mirage?

Rylan Schaeffer, Brando Miranda, Sanmi Koyejo. Stanford. NeurIPS 2023.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.15004

This paper questions the claim that LLMs have emergent abilities – unexpected skills that suddenly appear only with models that are sufficiently large. They show that this property is mostly due to the use of discontinuous metrics, which only credit models once they reach sufficiently high levels of abilities. When using smooth continuous metrics, and increasing test sets to sufficient size, the “sudden appearance” of abilities is replaced by gradual improvements.

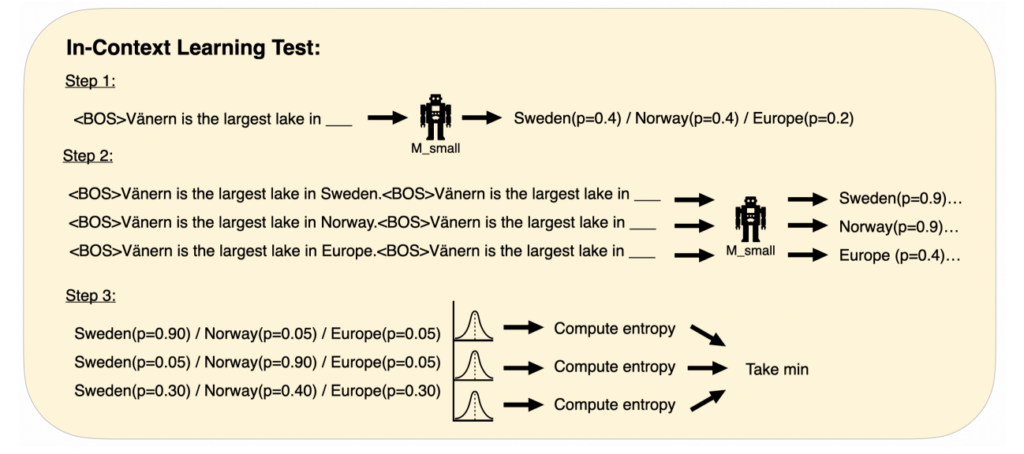

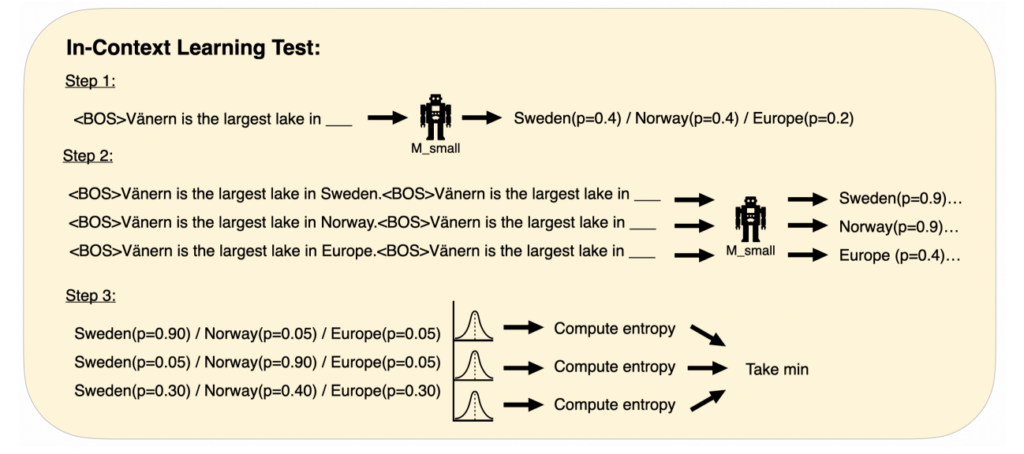

9. Distinguishing the Knowable from the Unknowable with Language Models

Gustaf Ahdritz, Tian Qin, Nikhil Vyas, Boaz Barak, Benjamin L. Edelman. Harvard. ICML 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.03563

The paper investigates the possibility of distinguishing epistemic uncertainty (due to lack of knowledge) from aleatoric uncertainty (due to entropy in the underlying distribution) in LLMs. They make the assumption that a large LLM has no (or less) epistemic uncertainty and train a probe to predict the uncertainty of a large LLM based on the frozen activations of a smaller LLM. This is largely successful, indicating that the model activations in the smaller model are able to differentiate between the different uncertainty types. They also propose that in-context information affects the LLM probabilities more in the case of epistemic uncertainty, and less with aleatoric uncertainty.

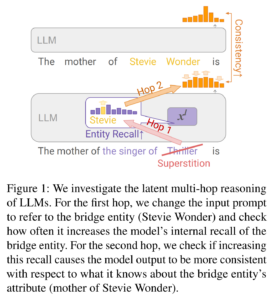

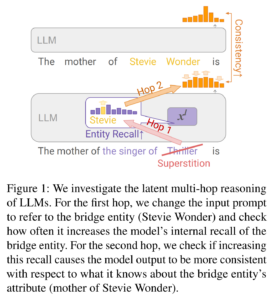

10. Do Large Language Models Latently Perform Multi-Hop Reasoning?

Sohee Yang, Elena Gribovskaya, Nora Kassner, Mor Geva, Sebastian Riedel. DeepMind, UCL, Google Research, Tel Aviv University. ArXiv 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.16837

The paper investigates the ability of LLMs to perform latent multi-hop reasoning, by completing sentences such as “The author of the novel Ubik was born in the city of …”. They construct experiments to investigate each hop separately: 1) whether the internal representation for the intermediate entity (“Philip K. Dick”) required for the first hop strengthens, and 2) whether increased recall of the intermediate entity improves the consistency of the final answer. In these experiments they find strong evidence for the first hop and moderate evidence for the second hop. They construct a dataset of 45,595 pairs of one-hop and two-hop prompts, to be released.

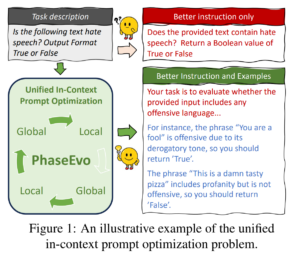

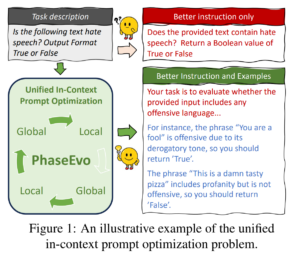

11. PhaseEvo: Towards Unified In-Context Prompt Optimization for Large Language Models

Wendi Cui, Jiaxin Zhang, Zhuohang Li, Hao Sun, Damien Lopez, Kamalika Das, Bradley Malin, Sricharan Kumar. Intuit, Vanderbilt, Cambridge. ArXiv 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.11347

The paper describes an evolution strategy for finding optimal LLM prompts for specific tasks. Prompts are first initialised either by experts or by asking an LLM to recover the prompt based on example input-output pairs. These initial prompts then go through multiple mutation steps, by having the LLM rewrite the prompts according to different strategies. The fitness of the prompts is measured by performance on the dev set and the best prompt is then evaluated on the test set.

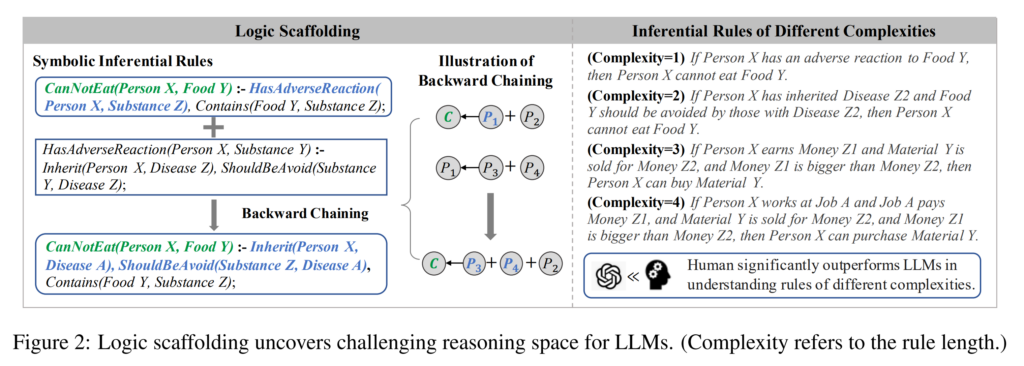

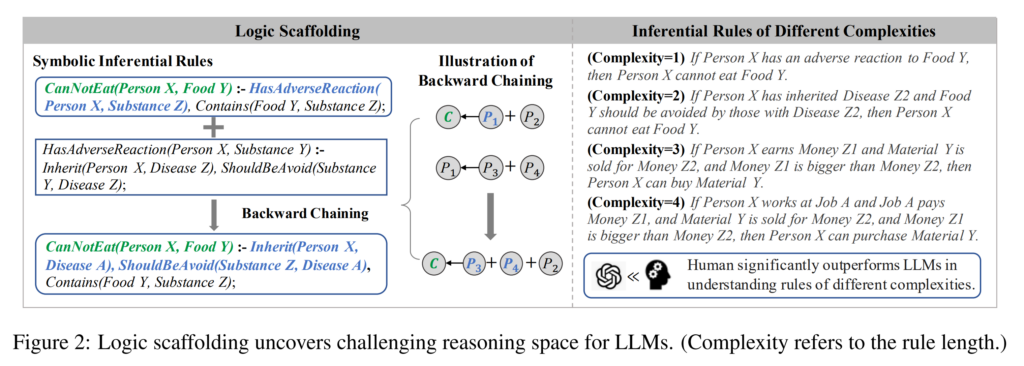

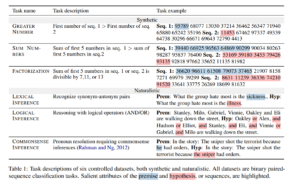

12. Can LLMs Reason with Rules? Logic Scaffolding for Stress-Testing and Improving LLMs

Siyuan Wang, Zhongyu Wei, Yejin Choi, Xiang Ren. Fudan University, University of Washington, USC, AllenAI. ArXiv 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.11442

The paper first constructs a dataset of 14000 commonsense logical rules, using LLMs to generate and check the rules. They then assess LLM understanding of these rules by turning the rules into a binary entailment classification task, showing that all models decrease in performance as the complexity of the rules increases. Finally, they train an LLM with these rules and show benefit on downstream tasks that require commonsense reasoning.

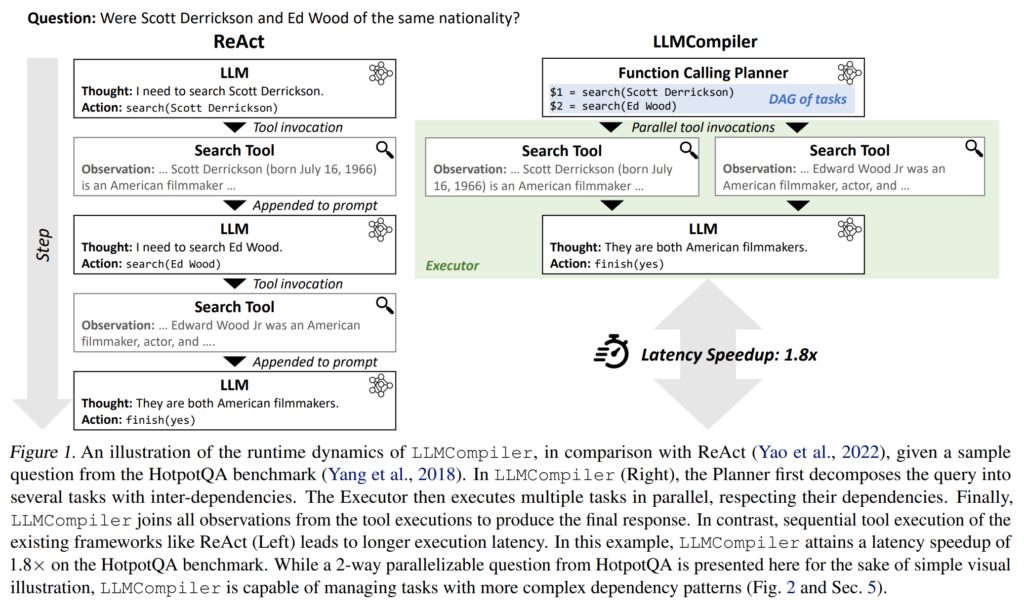

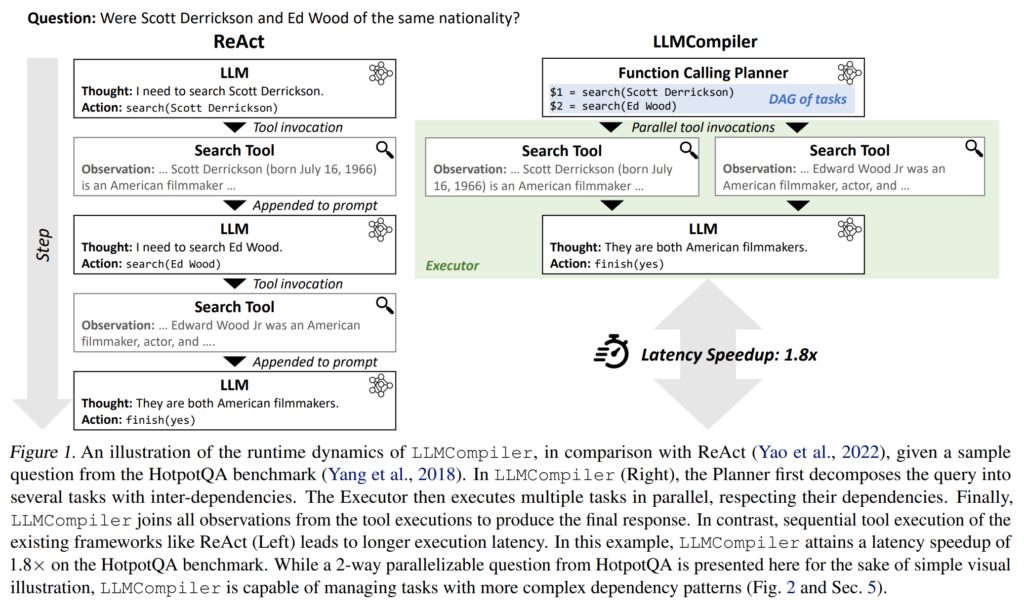

13. An LLM Compiler for Parallel Function Calling

Sehoon Kim, Suhong Moon, Ryan Tabrizi, Nicholas Lee, Michael W. Mahoney, Kurt Keutzer, Amir Gholami. UC BErkeley, ICSI, LBNL. ICML 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.04511

While most LLMs perform tool calls sequentially, in a linear iteration loop, this paper investigates executing tool calls in parallel. The planner stage first predicts which tool calls will be needed and what are the dependencies between the tool calls. These tools are then called in parallel and the results are then combined for the final answer. They show performance improvements in some settings and speed improvements in all evaluated settings, showing particular usefulness in settings where the LLM needs to retrieve information about multiple entities (e.g. do background research) in order to reach the final solution.

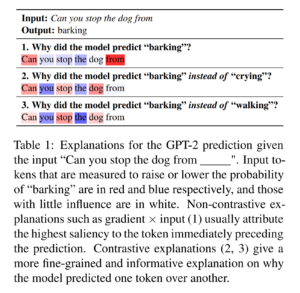

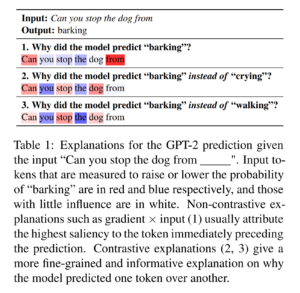

14. Interpreting Language Models with Contrastive Explanations

Kayo Yin, Graham Neubig. UC Berkeley, CMU. EMNLP 2022.

https://aclanthology.org/2022.emnlp-main.14/

Proposes an explainability method for language modelling that explains why one word was predicted instead of a specific other word. Adapts three different explainability methods to this contrastive approach and evaluates on a dataset of minimally different sentences. The method is shown to better highlight the differences between these specific words, instead of just assigning most of the focus to the previous word.

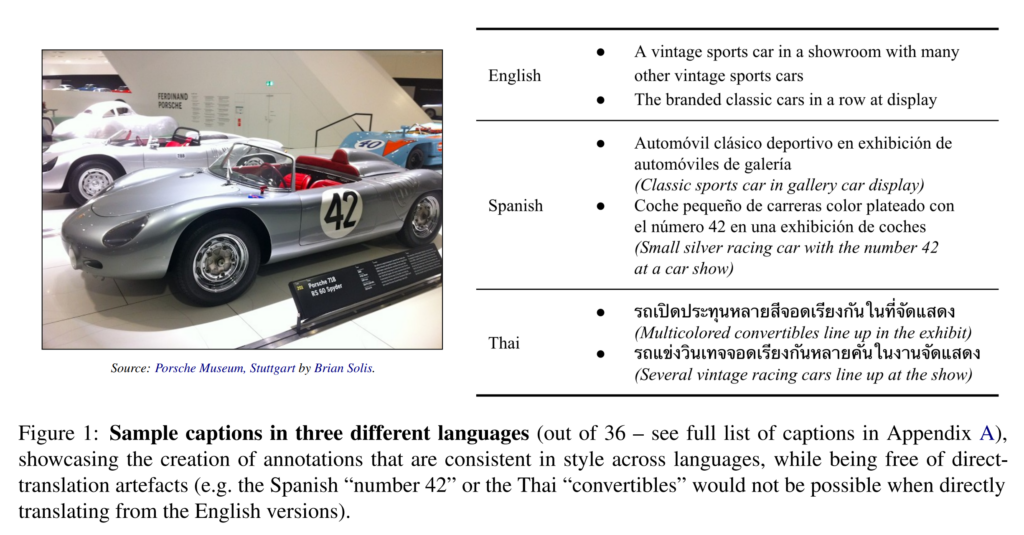

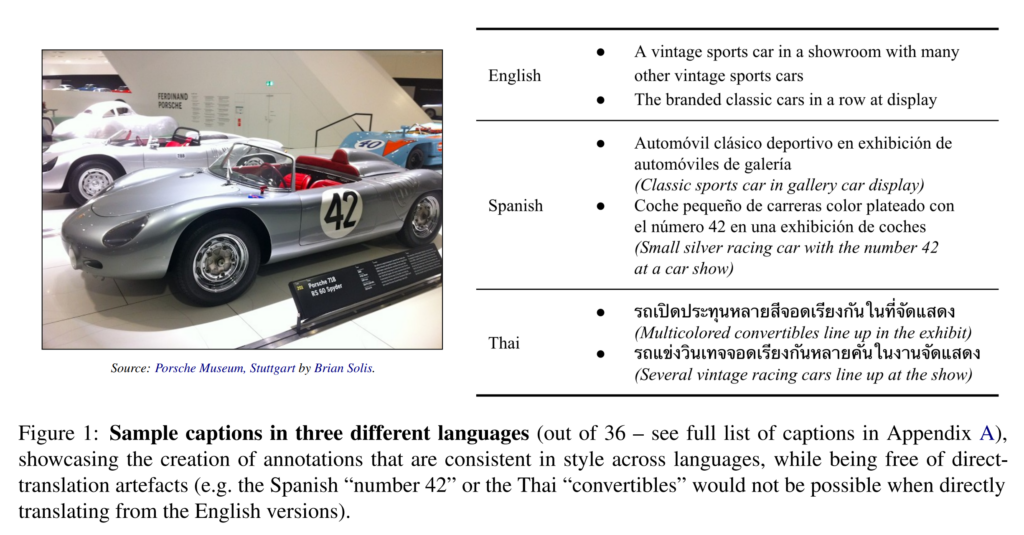

15. Crossmodal-3600: A Massively Multilingual Multimodal Evaluation Dataset

Ashish V. Thapliyal, Jordi Pont-Tuset, Xi Chen, Radu Soricut. Google Research. EMNLP 2022.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.12522

Multilingual image captioning dataset containing captions in 36 languages for 3600 images. An annotation process has been designed to make sure all the annotations resemble the same style, similar to an automated captioning output. Results show that the dataset provides a much higher correlation to human judgements, compared to the silver annotations from COCO-dev.

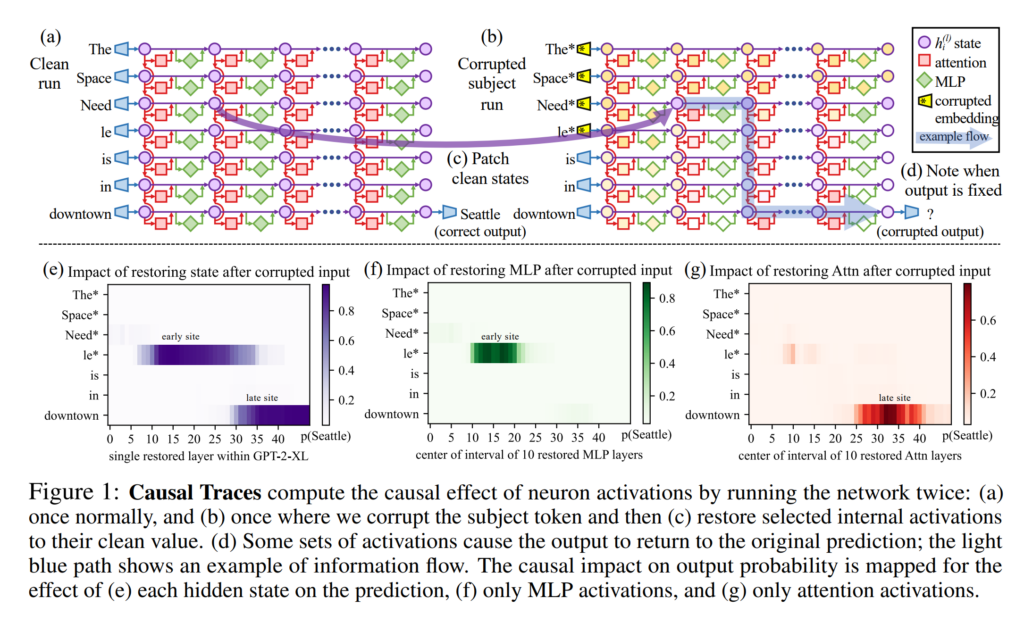

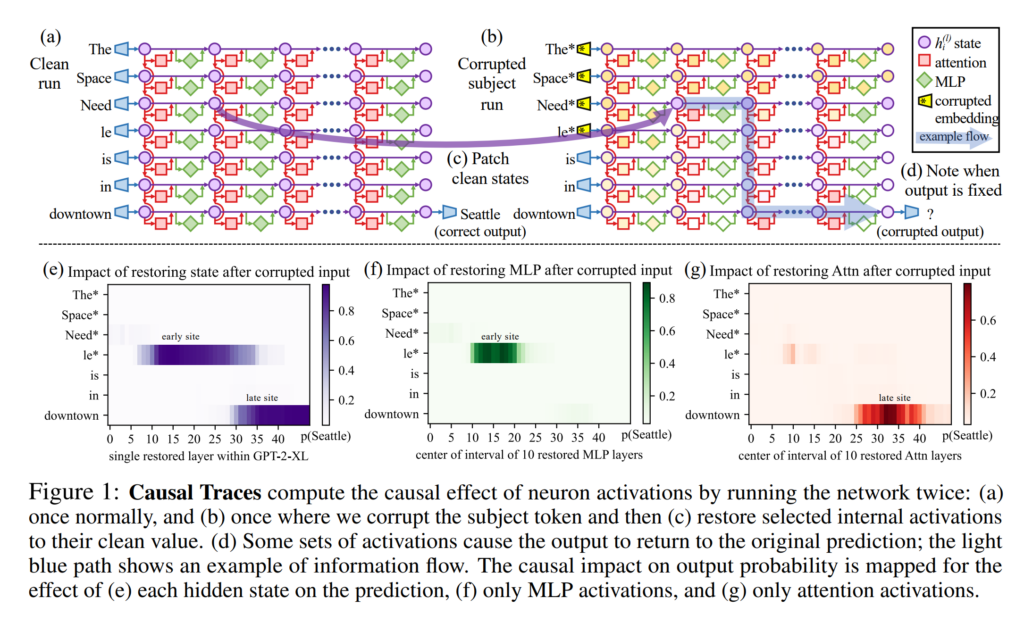

16. Locating and Editing Factual Associations in GPT

Kevin Meng, David Bau, Alex Andonian, Yonatan Belinkov. MIT, Northeastern, Technion IIT. NeurIPS 2022.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2202.05262

Proposes a method for editing a specific relational fact in a pre-trained language model. The specific feedforward layer that is responsible for recalling the target of a specific fact is identified using noisy permutations of the model activations. The feedforward layer is then directly trained to produce a more optimal output when given the subject of that fact as input.

17. M2D2: A Massively Multi-Domain Language Modeling Dataset

Machel Reid, Victor Zhong, Suchin Gururangan, Luke Zettlemoyer. The University of Tokyo, University of Washington. EMNLP 2022.

https://aclanthology.org/2022.emnlp-main.63/

Assembling a dataset for language model domain adaptation, from Wikipedia and ArXiv, containing 22 broad domains and 145 fine-grained domains. Experiments show that when fine-tuning a model for in-domain data, it is best to tune on related broad domain data first, then further only on the specific fine-grained domain data. Out-of-domain performance is shown to strongly correlate with vocabulary overlap between the different domains.

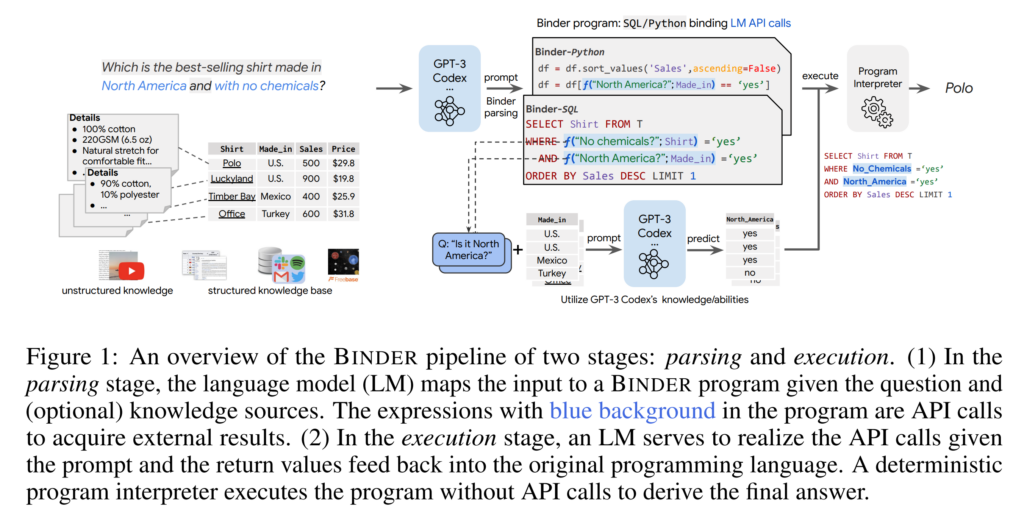

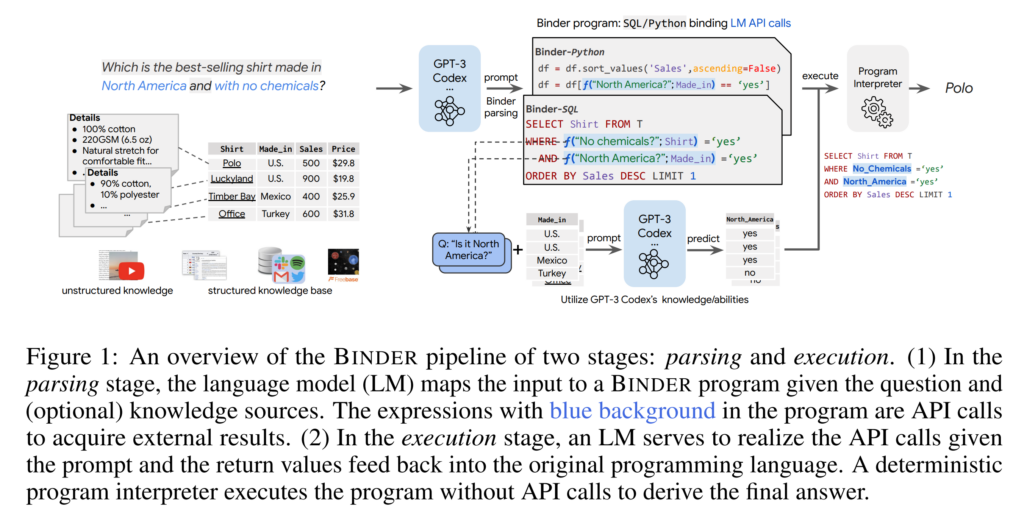

18. Binding Language Models in Symbolic Languages

Zhoujun Cheng, Tianbao Xie, Peng Shi, Chengzu Li, Rahul Nadkarni, Yushi Hu, Caiming Xiong, Dragomir Radev, Mari Ostendorf, Luke Zettlemoyer, Noah A. Smith, Tao Yu. The University of Hong Kong, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, University of Washington, AllenAI, University of Waterloo, Salesforce Research, Yale University, Meta AI. ICLR 2023.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.02875

Uses a large pre-trained language model (GPT-3 Codex) to translate a natural language question into an SQL query. This query can then contain API calls, which also get executed by the language model, in order to populate additional columns of information in a database, over which the SQL can then operate. Outperforms previous methods on datasets of questions about data tables, using only contextual examples without fine-tuning the language model.

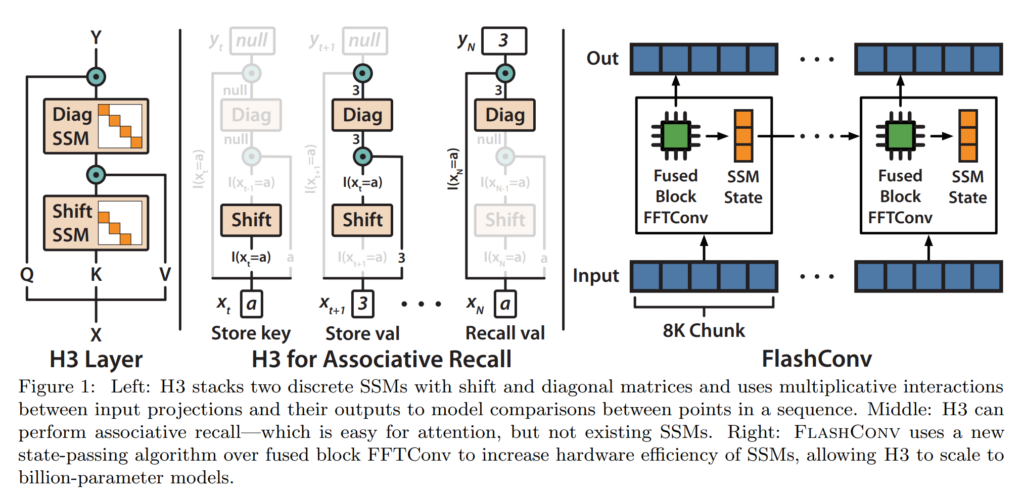

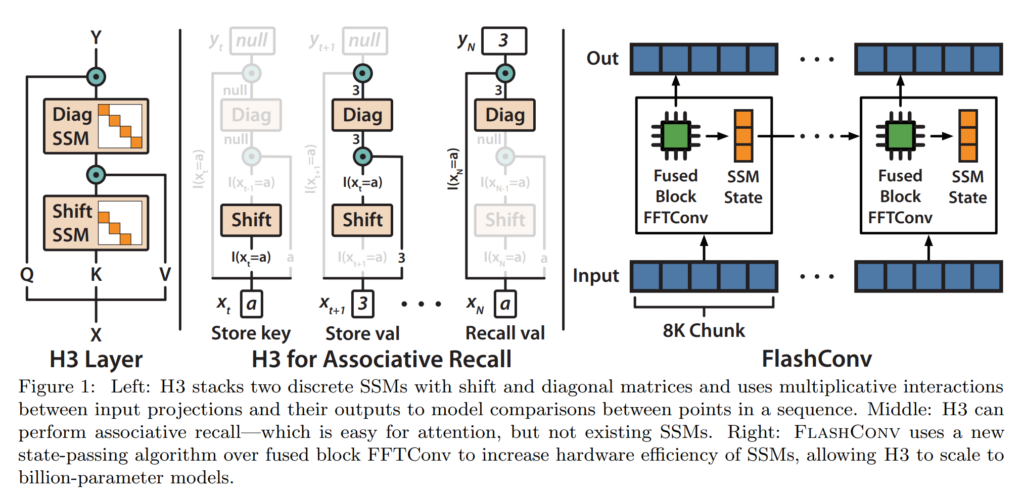

19. Hungry Hungry Hippos: Towards Language Modeling with State Space Models

Daniel Y. Fu, Tri Dao, Khaled K. Saab, Armin W. Thomas, Atri Rudra, Christopher Ré. Stanford, University at Buffalo. ICLR 2023.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.14052

Proposes a modification for state space models, a version of RNN with linear operations that can be separated into components of cumulative sums. The modification gives them abilities similar to attention, being able to copy and compare tokens across the sequence. The architecture scales O(N log N) with sequence length N, as opposed to N^2 for regular attention.

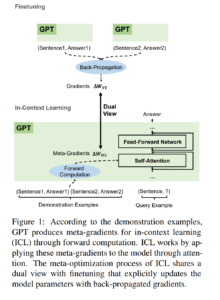

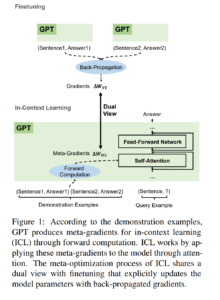

20. Why Can GPT Learn In-Context? Language Models Implicitly Perform Gradient Descent as Meta-Optimizers

Damai Dai, Yutao Sun, Li Dong, Yaru Hao, Shuming Ma, Zhifang Sui, Furu Wei. ACL 2023.

https://aclanthology.org/2023.findings-acl.247/

Shows how the equations for attention during in-context learning (showing the model examples in the input) can be thought of as a form of gradient descent. Experiments indicate that there are also similarities in how these methods affect the model in practice.

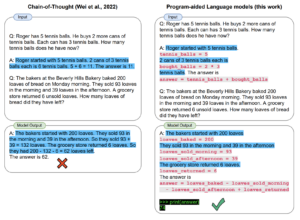

21. PAL: Program-aided Language Models

Luyu Gao, Aman Madaan, Shuyan Zhou, Uri Alon, Pengfei Liu, Yiming Yang, Jamie Callan, Graham Neubig. CMU, Inspired Cognition. ICML 2023.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.10435

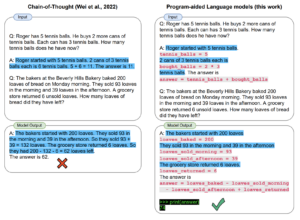

Question answering with a language model while generating a chain-of-thought, outputting the necessary reasoning steps to get to the answer. In addition to natural language reasoning steps, the model generates python syntax that is then executed in order to output the final answer. This is shown to improve results, particularly when the result requires mathematical arithmetic over large numbers.

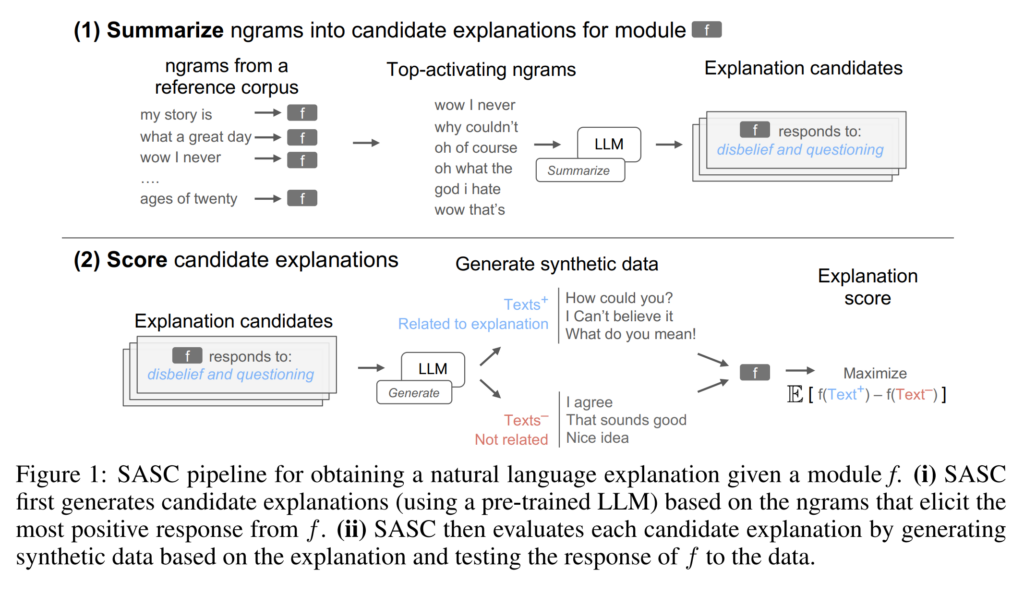

22. Explaining black box text modules in natural language with language models

Chandan Singh, Aliyah R. Hsu, Richard Antonello, Shailee Jain, Alexander G. Huth, Bin Yu, Jianfeng Gao. MSR, UC Berkeley, UT Austin. NeurIPS XAIA 2023.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.09863

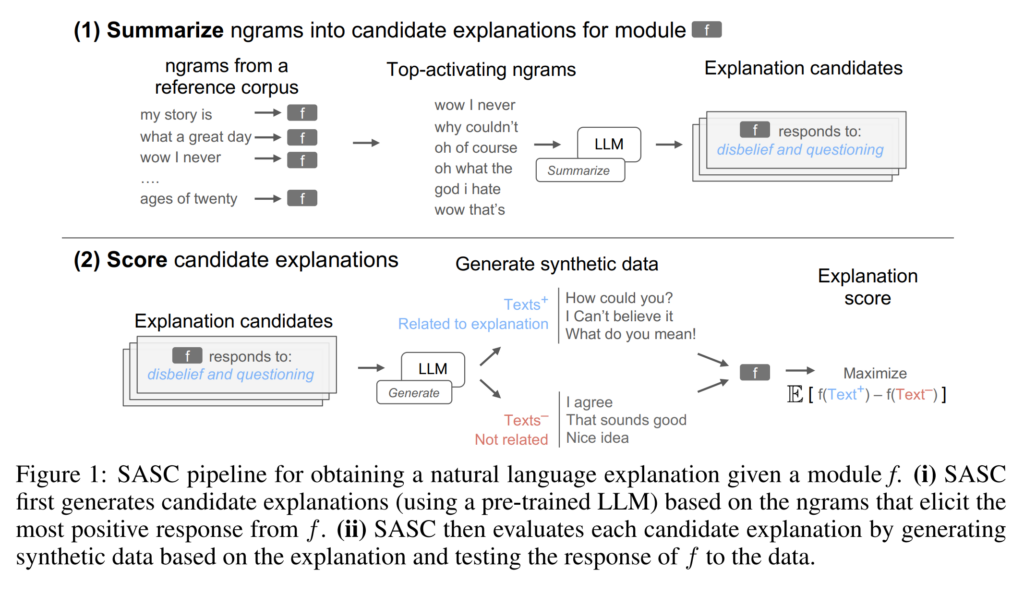

A method for providing natural language explanations to black-box modules that take neurons as input and return a score as output. A large number of ngrams are passed through the model in order to identify ngrams that result in the largest score. These ngrams are sampled and fed into an LLM for summarization, generating explanation candidates. An LLM is then used for generating positive and negative example sentences based on each candidate explanation, and the score differences between these examples are used for selecting the best explanation.

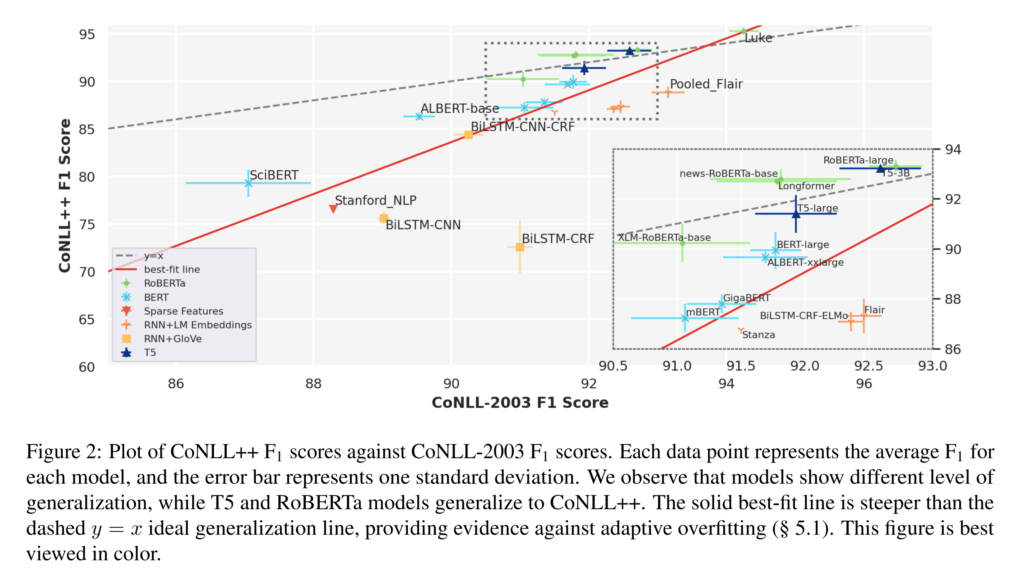

23. Do CoNLL-2003 Named Entity Taggers Still Work Well in 2023?

Shuheng Liu, Alan Ritter. Georgia Institute of Technology. ACL 2023.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.09747

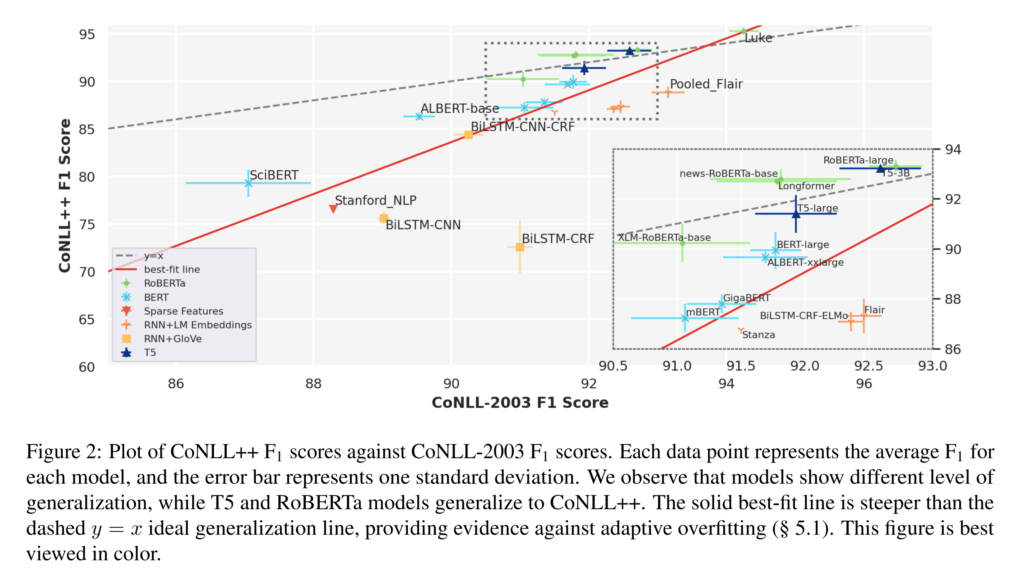

A thorough investigation of well-known NER models and how their performance is affected on modern data when trained on CoNLL 2003. They annotate a new test set of news data from 2020 and find that performance of certain models holds up very well and the field luckily hasn’t overfitted to the CoNLL 2003 test set. For best results on modern data, large models pre-trained on contemporary corpora come out on top, with RoBERTa, T5 and LUKE standing out.

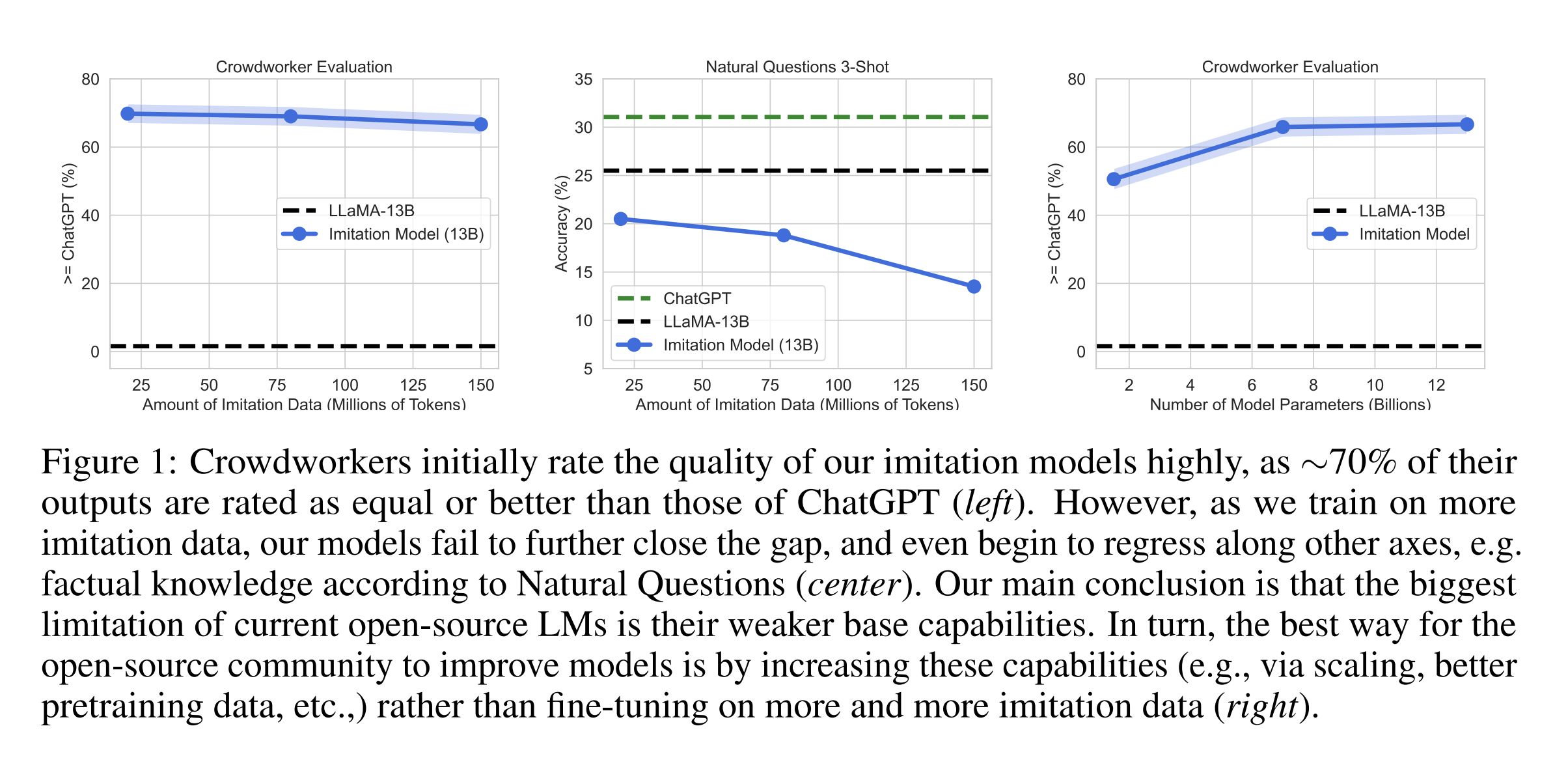

24. The False Promise of Imitating Proprietary LLMs

Arnav Gudibande, Eric Wallace, Charlie Snell, Xinyang Geng, Hao Liu, Pieter Abbeel, Sergey Levine, Dawn Song. UC Berkeley. ArXiv 2023.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.15717

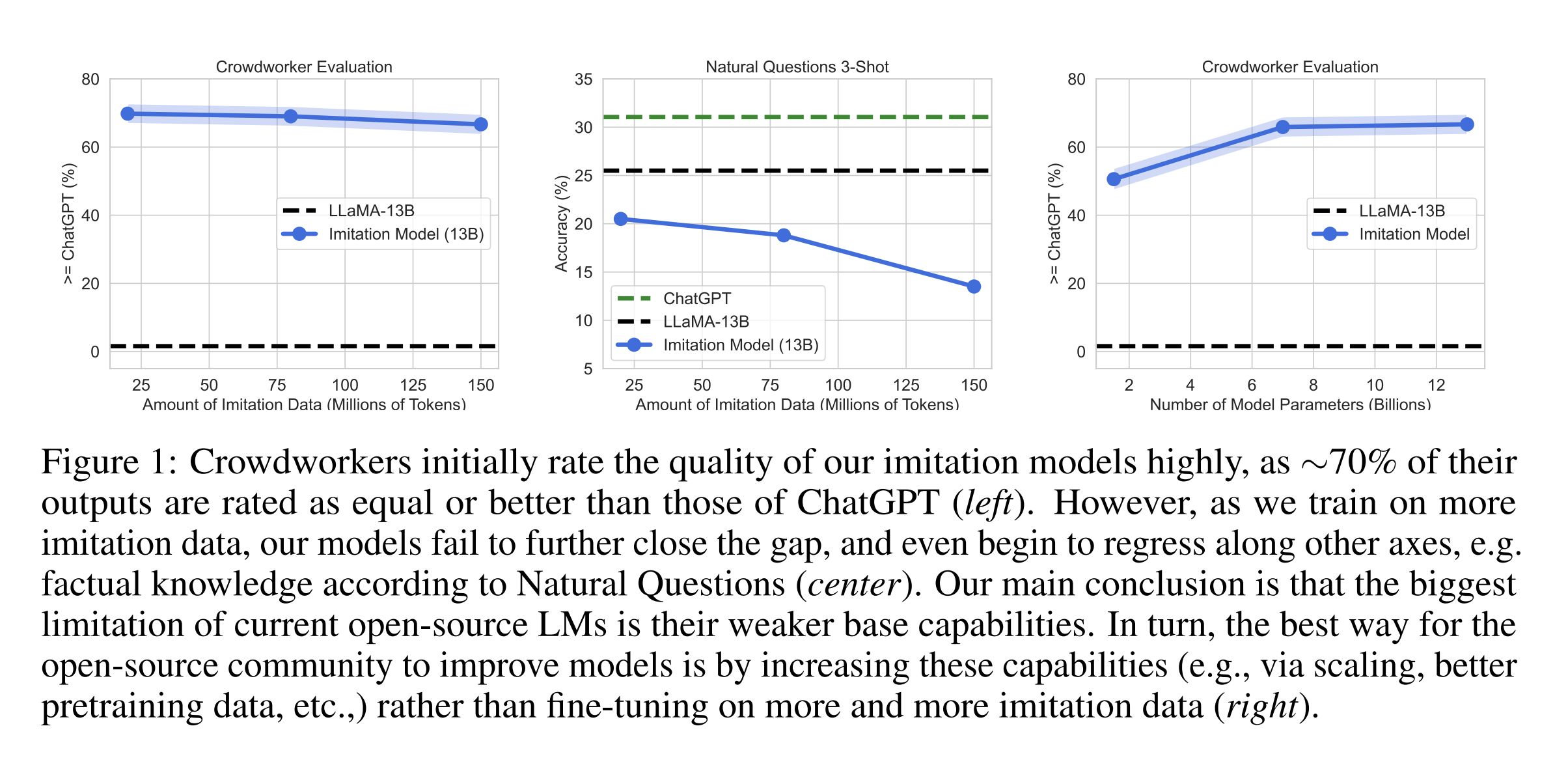

Analyzing the performance of open-source LLMs fine-tuned on the outputs of proprietary LLMs. They conclude that when fine-tuned on general-purpose dialogues, the models learn to mimic the style of the teacher model and can fool human assessors, but lack core knowledge and can more easily generate factually incorrect claims. However, when fine-tuning only for a specific task, then this imitation strategy can reach near-parity with the teacher models.

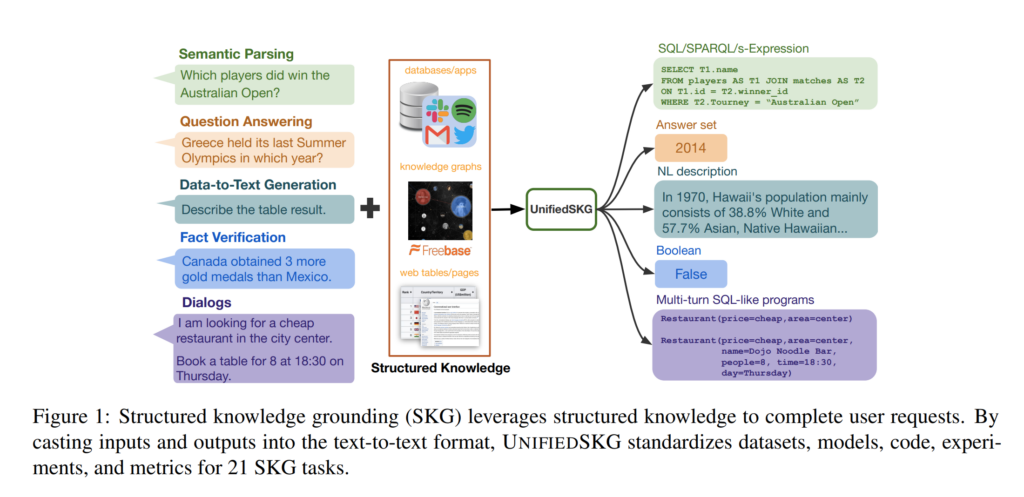

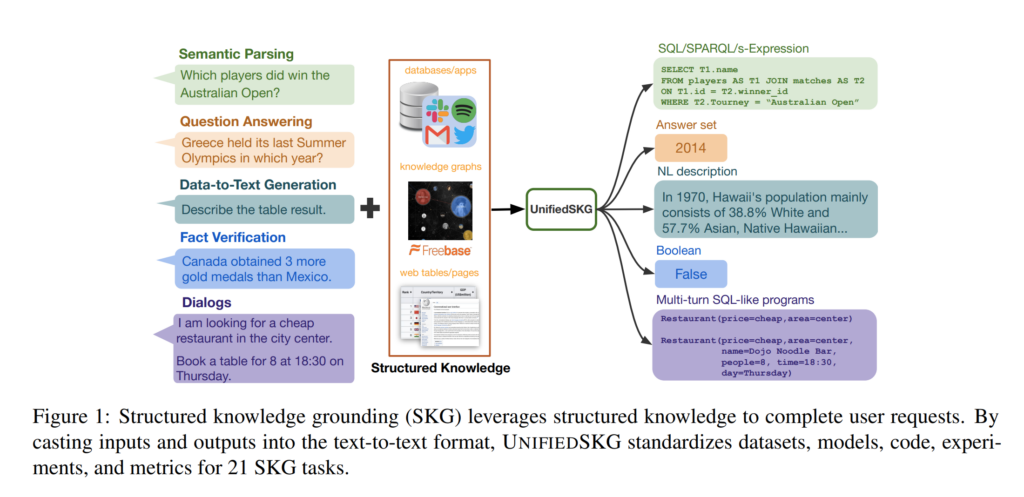

25. UnifiedSKG: Unifying and Multi-Tasking Structured Knowledge Grounding with Text-to-Text Language Models

Tianbao Xie, Chen Henry Wu, Peng Shi, Ruiqi Zhong, Torsten Scholak, Michihiro Yasunaga, Chien-Sheng Wu, Ming Zhong, Pengcheng Yin, Sida I. Wang, Victor Zhong, Bailin Wang, Chengzu Li, Connor Boyle, Ansong Ni, Ziyu Yao, Dragomir Radev, Caiming Xiong, Lingpeng Kong, Rui Zhang, Noah A. Smith, Luke Zettlemoyer, Tao Yu. Misc. EMNLP 2022.

https://aclanthology.org/2022.emnlp-main.39

Unifies 21 generation tasks that require accessing structured information sources into a general sequence-to-sequence benchmark for language models. It includes datasets on semantic parsing, question answering, data-to-text, dialogue and fact verification. The input, structured data and and output is linearised for these datasets, so that a general-purpose language model can be used for all of them. A fine-tuned T5 model is shown to outperform existing SOTA models on many of these datasets.

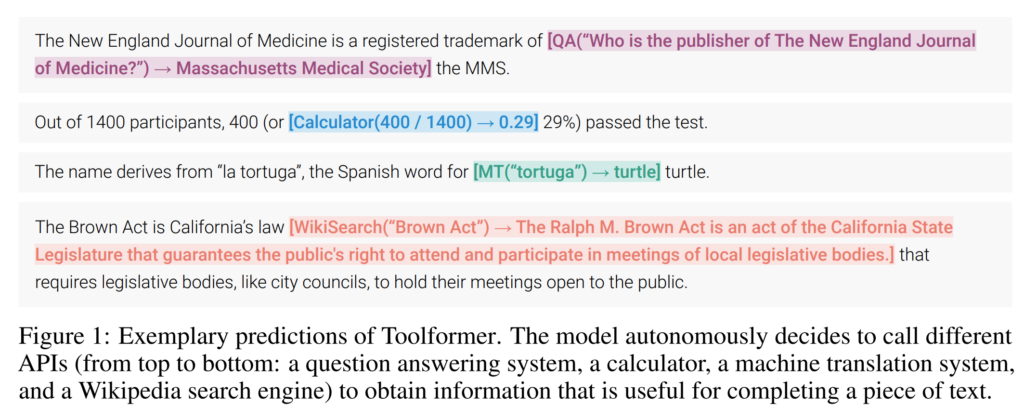

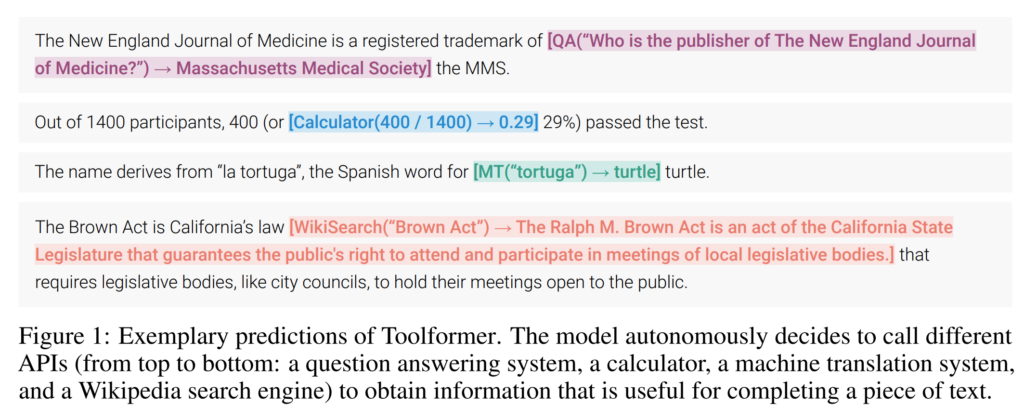

26. Toolformer: Language Models Can Teach Themselves to Use Tools

Timo Schick, Jane Dwivedi-Yu, Roberto Dessì, Roberta Raileanu, Maria Lomeli, Luke Zettlemoyer, Nicola Cancedda, Thomas Scialom. Meta, Universitat Pompeu Fabra. NeurIPS 2023.

https://openreview.net/forum?id=Yacmpz84TH

The paper describes a method for teaching large language models to use external tools. A supervised dataset is created by trying to insert results from API calls into various points in the text, then only retaining the cases where doing that improves perplexity. The LM is then fine-tuned on this dataset and manages to improve performance on several tasks by using tools such as a QA system, Wikipedia search and a calculator.

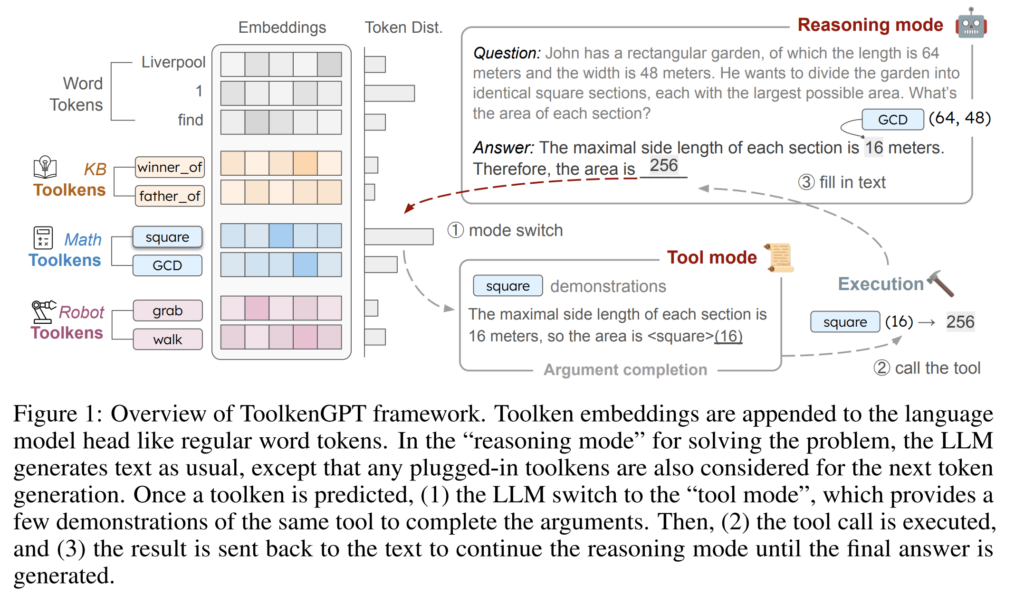

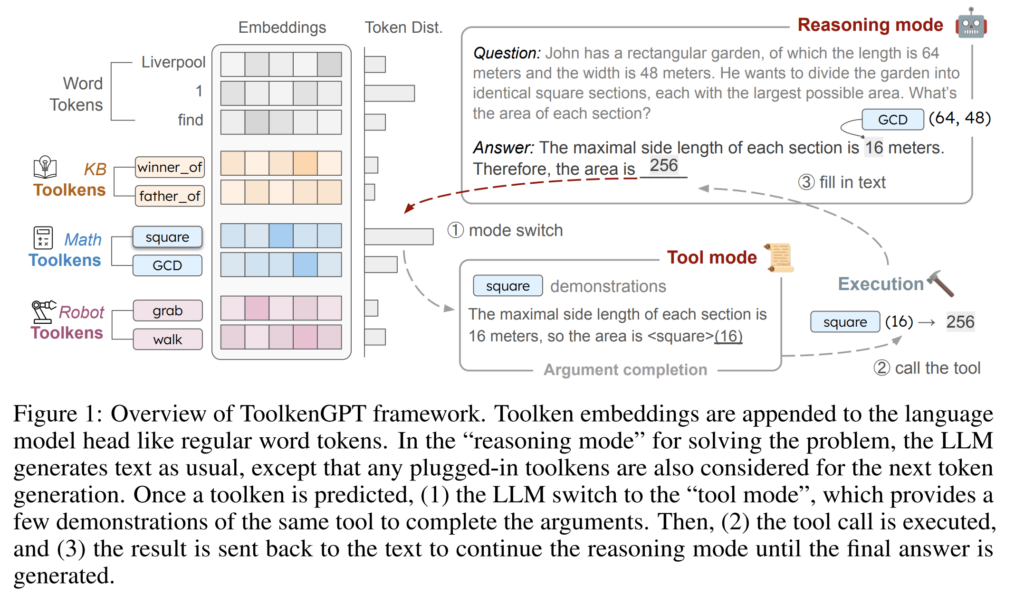

27. ToolkenGPT: Augmenting Frozen Language Models with Massive Tools via Tool Embeddings

Shibo Hao, Tianyang Liu, Zhen Wang, Zhiting Hu. UC San Diego, Mohamed bin Zayed University of Artificial Intelligence. NeurIPS 2023.

https://openreview.net/forum?id=BHXsb69bSx

The paper presents ToolkenGPT, a framework for extending LMs with tool use. For each new tool, a new token is added to the output vocabulary of the LM and the embedding for that token is trained with annotated or synthetic examples. When the LM generates that token, the model is switched to a different mode and prompted with examples for that particular tool in order to generate the necessary arguments for that tool call.

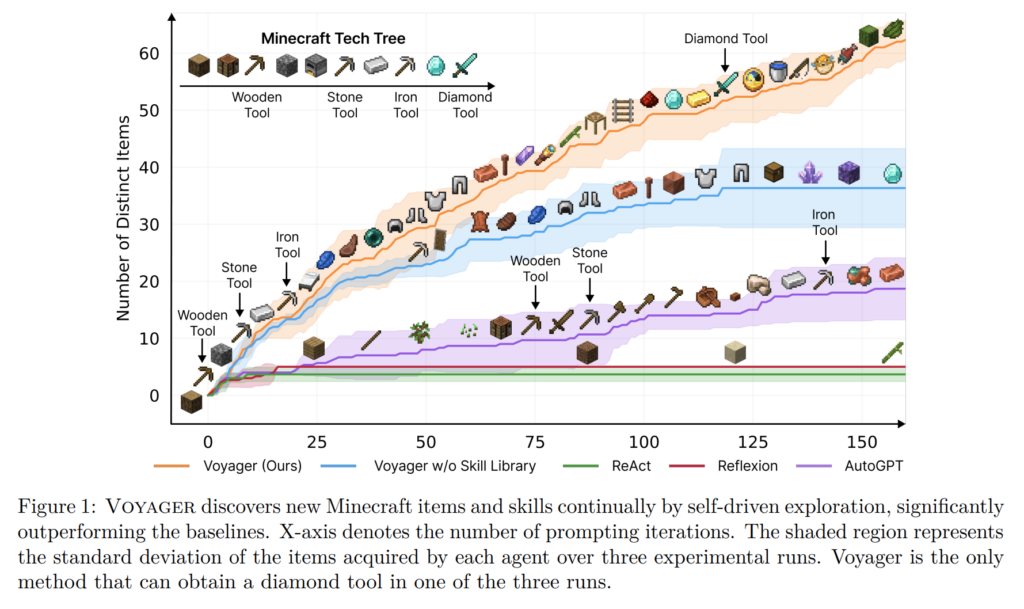

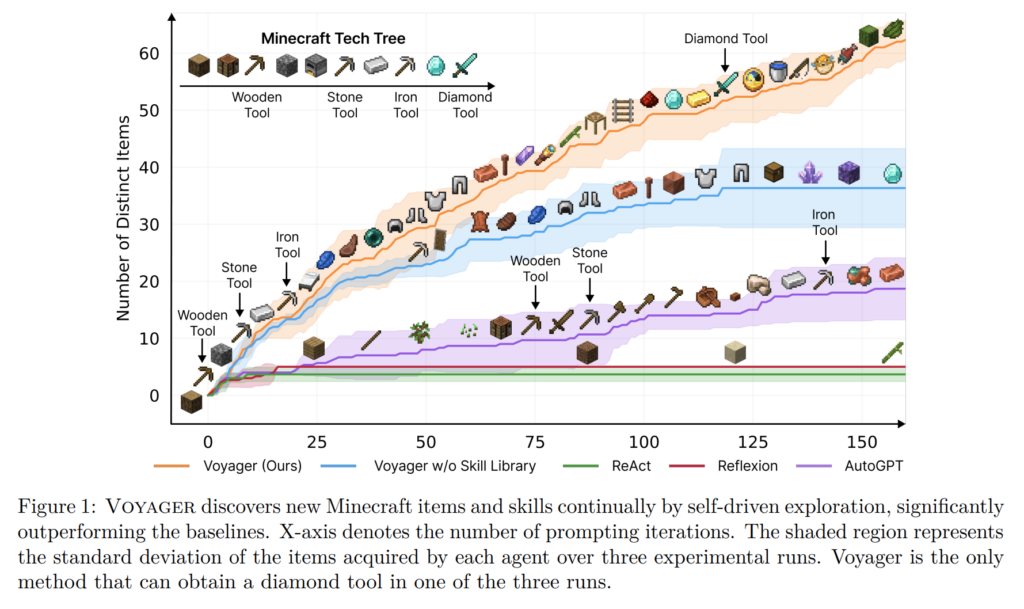

28. Voyager: An Open-Ended Embodied Agent with Large Language Models

Guanzhi Wang, Yuqi Xie, Yunfan Jiang, Ajay Mandlekar, Chaowei Xiao, Yuke Zhu, Linxi Fan, Anima Anandkumar. NVIDIA, Caltech, UT Austin, Stanford, UW Madison. TMLR 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.16291

Combining together black-box LLMs through different prompting strategies to create a capable agent for playing Minecraft. One component receives information about the current state, reasons about the next possible goals and formulates a suitable task in natural language. Another component receives the desired task along with descriptions of existing API functions and skills, then iteratively generates and improves a code function for performing that task.

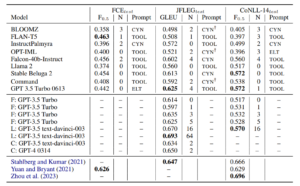

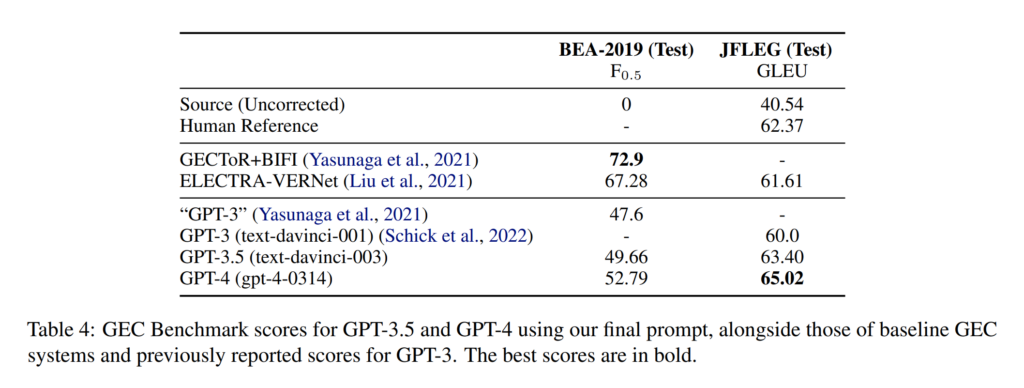

29. Analyzing the Performance of GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 in Grammatical Error Correction

Steven Coyne, Keisuke Sakaguchi, Diana Galvan-Sosa, Michael Zock, Kentaro Inui. Tohoku University, RIKEN, Aix-Marseille University. ArXiv 2023.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.14342

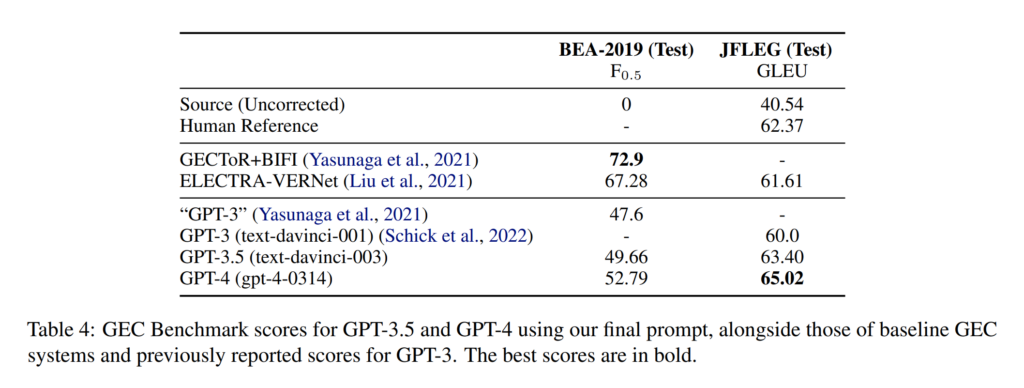

Evaluating well-known LLMs on two established benchmarks for grammatical error correction (GEC). They find that specific prompts matter quite a bit and lower temperature is better for GEC. The results show that LLMs tend to over-correct and perform fluency edits, achieving state-of-the-art performance on a dataset designed for this type of edits (JFLEG). However, performance is considerably lower on a benchmark that focuses on minimal edits and only fixing grammaticality (BEA-2019).

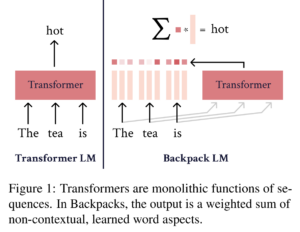

30. Backpack Language Models

John Hewitt, John Thickstun, Christopher D. Manning, Percy Liang. Stanford. ACL 2023.

https://aclanthology.org/2023.acl-long.506

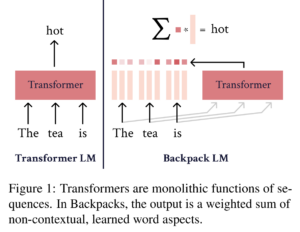

Proposes a language model architecture that maps each word to multiple sense vectors, uses a separate model to predict the weights for these senses, then directly outputs a prediction as a log-linear function. Experiments show that performance degrades, as many more parameters are required to reach a perplexity comparable to a transformer LM. They find that editing the weights of these sense vectors can be used for mitigating gender bias or editing specific information.

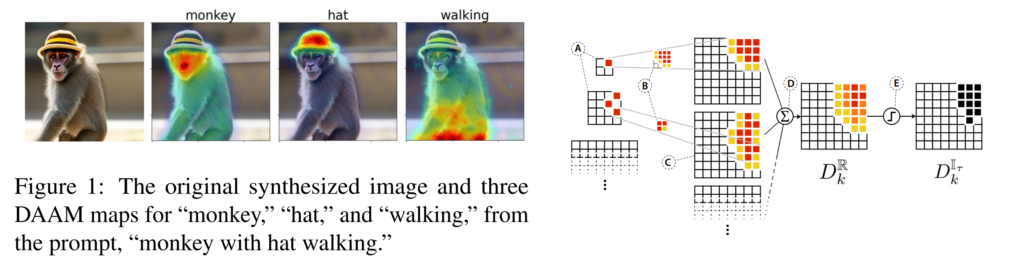

31. What the DAAM: Interpreting Stable Diffusion Using Cross Attention

Raphael Tang, Linqing Liu, Akshat Pandey, Zhiying Jiang, Gefei Yang, Karun Kumar, Pontus Stenetorp, Jimmy Lin, Ferhan Ture. Comcast Applied AI, UCL, University of Waterloo. ACL 2023.

https://aclanthology.org/2023.acl-long.310

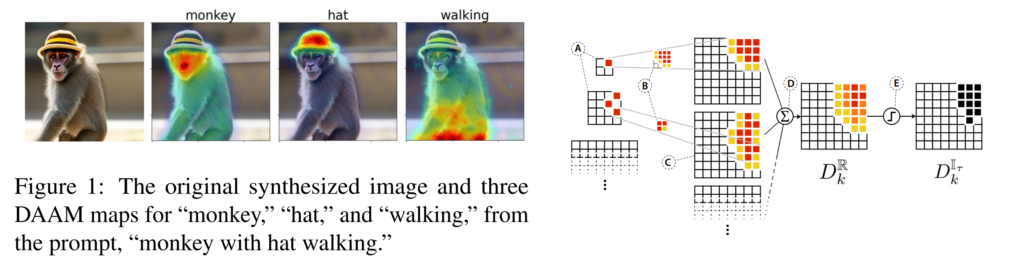

A method for analysing text-to-image models, indicating which areas of the generated image are attributed to a particular word in the input. They use the attention scores in Stable Diffusion between convolutional blocks and word embeddings, upscaling and aggregating them between different heads, layers and time steps. The result is competitive to supervised image segmentation models and they use it for linguistic analysis. For example, they show that cohyponyms (e.g. a giraffe and a zebra) in the input can have their concepts merged, resulting in only one of the objects being generated.

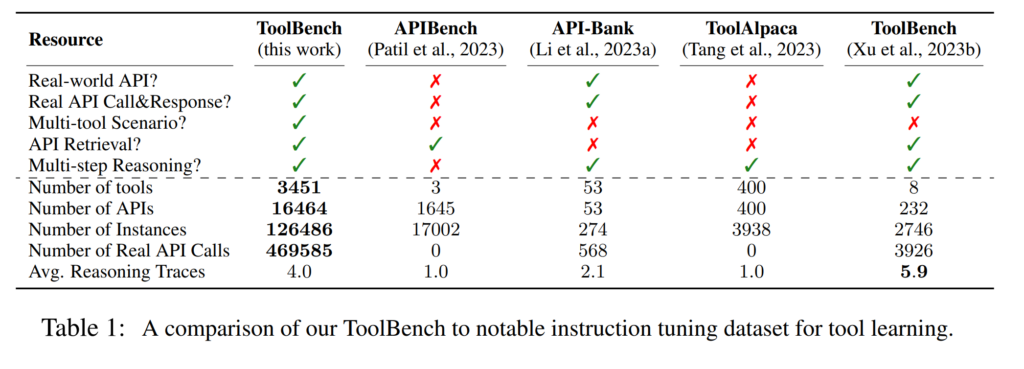

32. ToolLLM: Facilitating Large Language Models to Master 16000+ Real-world APIs

Yujia Qin, Shihao Liang, Yining Ye, Kunlun Zhu, Lan Yan, Yaxi Lu, Yankai Lin, Xin Cong, Xiangru Tang, Bill Qian, Sihan Zhao, Lauren Hong, Runchu Tian, Ruobing Xie, Jie Zhou, Mark Gerstein, Dahai Li, Zhiyuan Liu, Maosong Sun. Tsinghua University, ModelBest, Renmin University of China, Yale University, WeChat AI, Tencent, Zhihu. ICLR 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.16789

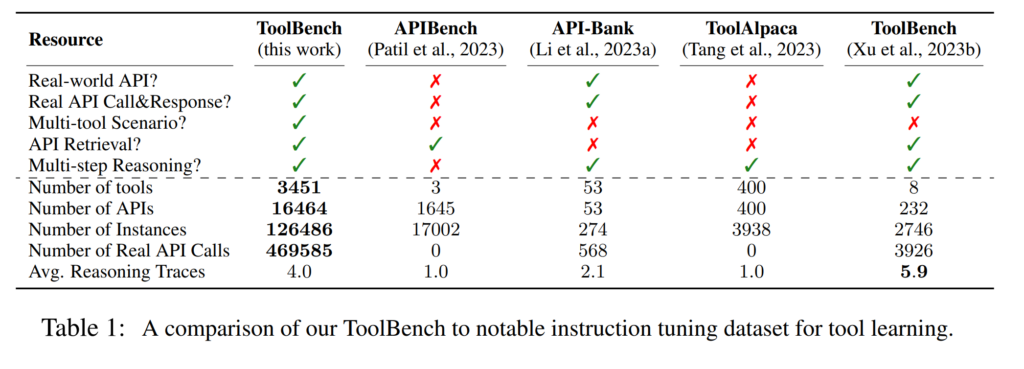

They crawl documentation for 16K APIs from RapidAPI and synthesize an instruction tuning dataset for using these APIs.

Instruction examples are generated using ChatGPT, by asking it to generate examples that make use of one or multiple sample APIs.

Multiple rounds of API calls and responses are allowed by the LLM, which are explored using a depth-first search strategy, until a final answer or termination is generated.

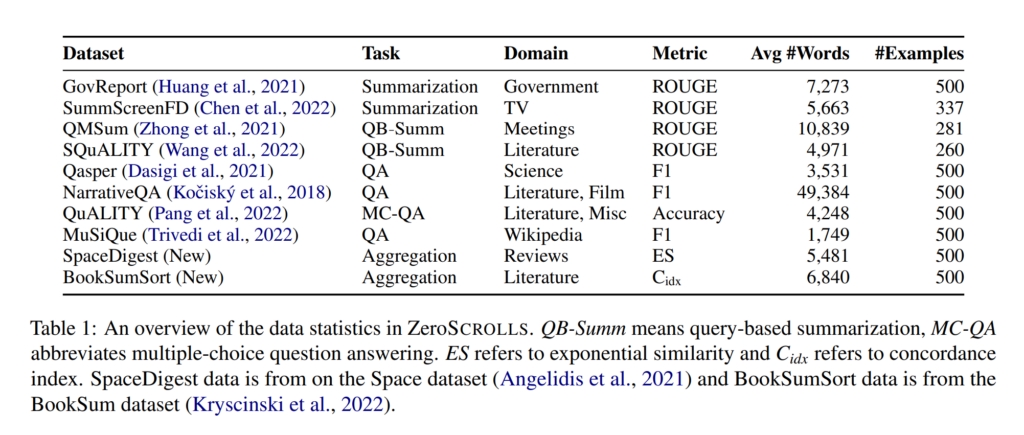

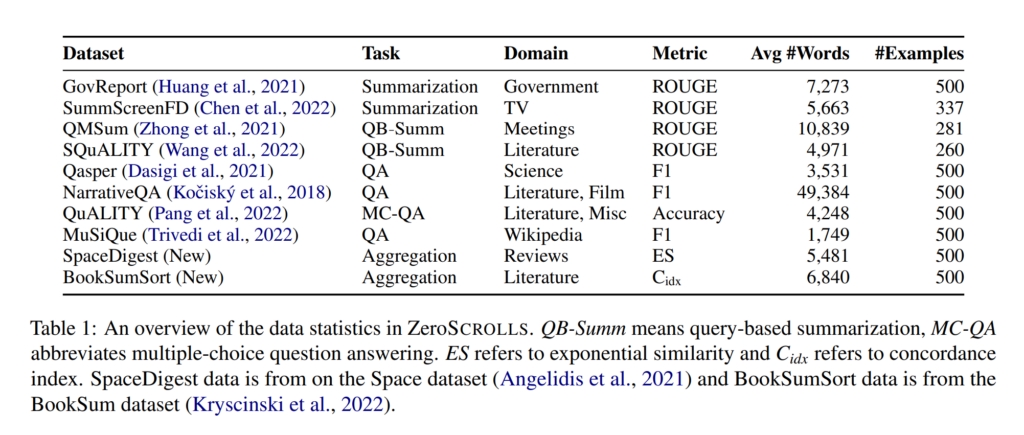

33. ZeroSCROLLS: A Zero-Shot Benchmark for Long Text Understanding

Uri Shaham, Maor Ivgi, Avia Efrat, Jonathan Berant, Omer Levy. Tel Aviv University, Meta AI. EMNLP 2023.

https://aclanthology.org/2023.findings-emnlp.536

Constructing a benchmark for zero-shot understanding of long texts with LLMs. Includes existing datasets (summarization, QA) from the Scrolls benchmark, along with two new tasks: determining the ratio of positive reviews in a set of reviews, and sorting a shuffled list of book chapter summaries. Results indicate that GPT-4 is best overall, even though it loses points in automatic evaluation as it doesn’t follow the instructed format.

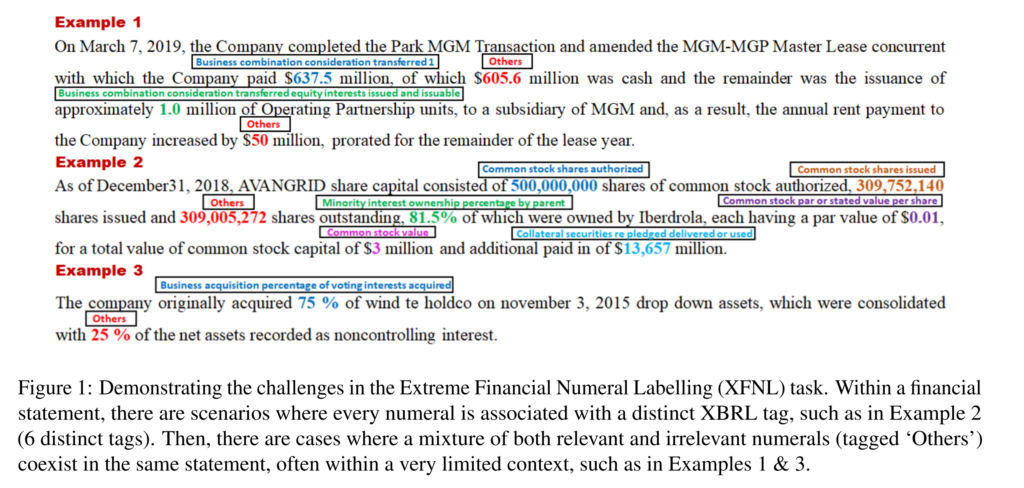

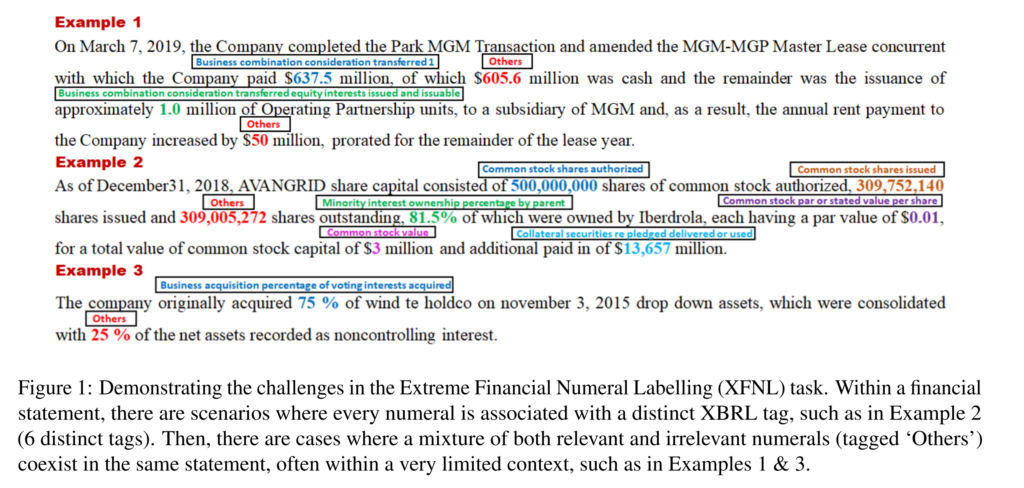

34. Parameter-Efficient Instruction Tuning of Large Language Models For Extreme Financial Numeral Labelling

Subhendu Khatuya, Rajdeep Mukherjee, Akash Ghosh, Manjunath Hegde, Koustuv Dasgupta, Niloy Ganguly, Saptarshi Ghosh, Pawan Goyal. Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, Goldman Sachs. NAACL 2024.

https://aclanthology.org/2024.naacl-long.410/

The paper approaches the task of tagging entities with a large number of labels using a generative model. The LLM is instruction-tuned to generate the label description of the label. The generated description is then mapped to the closest real label description using sentence embeddings and cosine similarity. The method achieves strong performance over other traditional tagging models on this task.

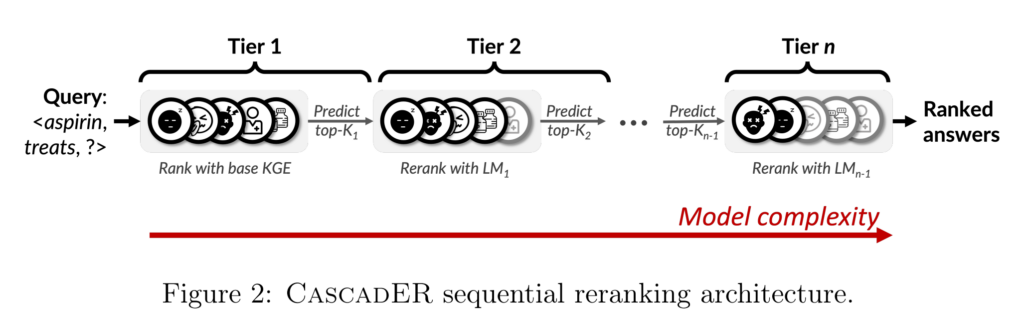

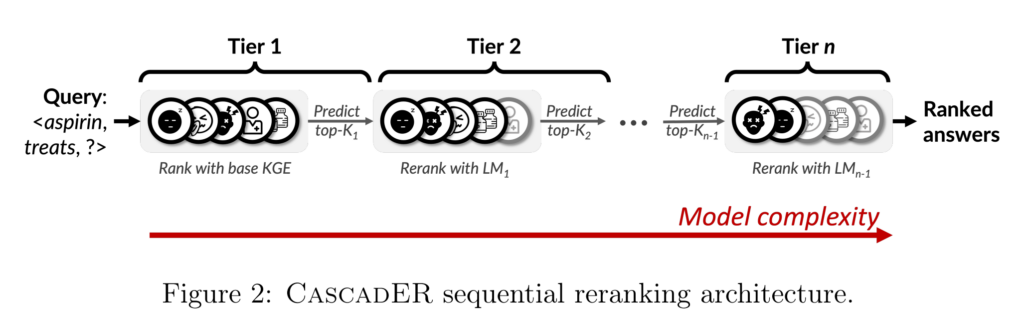

35. CascadER: Cross-Modal Cascading for Knowledge Graph Link Prediction

Tara Safavi, Doug Downey, Tom Hope. University of Michigan, Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, Northwestern University, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. AKBC 2022.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.08012

Proposes a pipeline of increasingly complex models for predicting links in graph. Simpler models are used to perform initial filtering, then more complex models that need much processing time are applied only on a small chosen sample. The number of candidates to retain at each stage is learned in a supervised way. The model makes it feasible to apply very large models to large tasks while also improving the SOTA results.

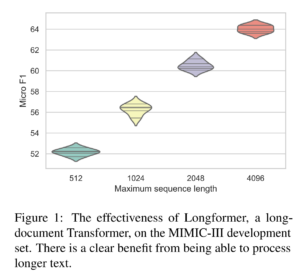

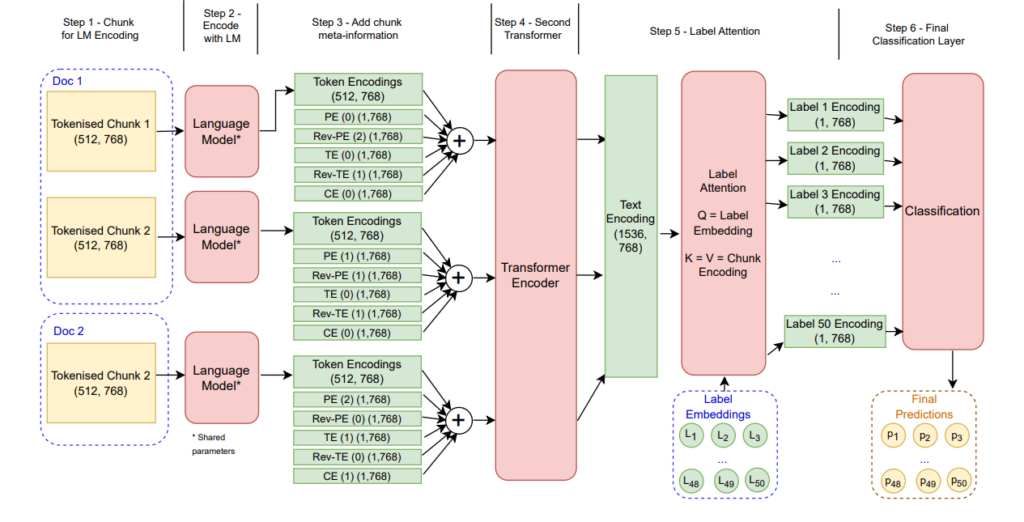

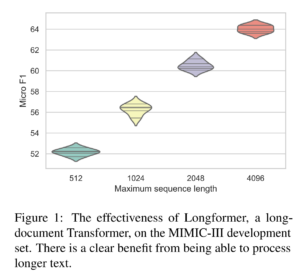

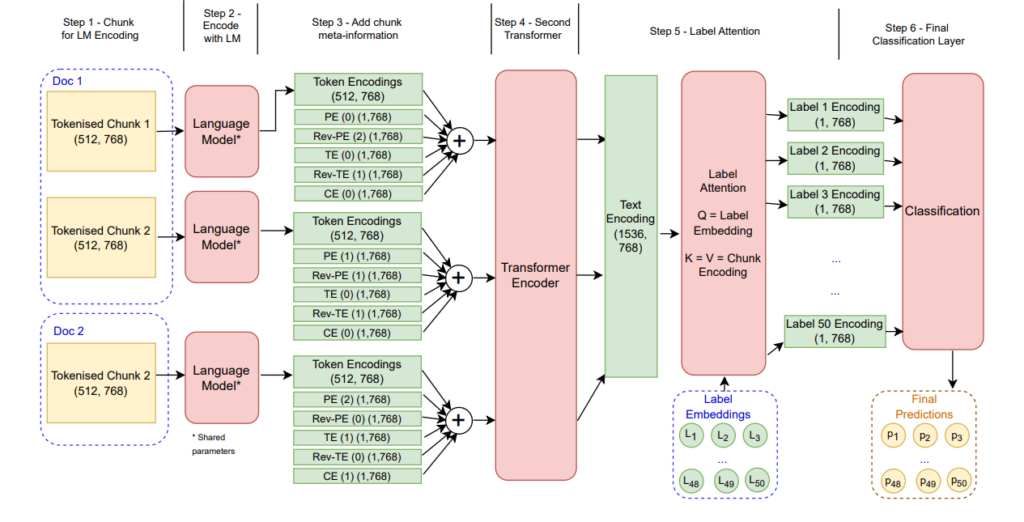

36. Revisiting Transformer-based Models for Long Document Classification

Xiang Dai, Ilias Chalkidis, Sune Darkner, Desmond Elliott. CSIRO Data61, University of Copenhagen. EMNLP 2022.

https://aclanthology.org/2022.findings-emnlp.534.pdf

Comparing sparse attention (Longformer) and hierarchical transformers for long document classification, focusing on electronic health records. They find that the performance is close, with Longformer slightly better out-of-the-box and hierarchical models better after tuning hyperparameters. Results also indicate that splitting long text into overlapping sections and using Label-Wise Attention Network helps improve performance.

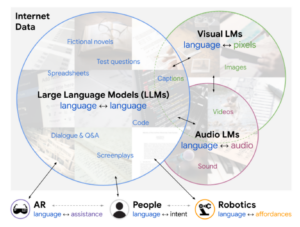

37. Socratic Models: Composing Zero-Shot Multimodal Reasoning with Language

Andy Zeng, Maria Attarian, Brian Ichter, Krzysztof Choromanski, Adrian Wong, Stefan Welker, Federico Tombari, Aveek Purohit, Michael Ryoo, Vikas Sindhwani, Johnny Lee, Vincent Vanhoucke, Pete Florence. Google. ICLR 2023.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.00598

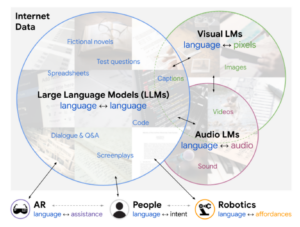

Constructs a pipeline of pre-trained language models with different modalities for scene understanding. Visual LMs rank possible locations and objects, audio LMs rank possible sounds, regular LMs take this information in a filled-out template and generate summaries or answers for QA. LMs can also be used to generate candidate activities, based on the detected places and objects, then these activities are re-ranked by a visual LM to choose ones that match the scene.

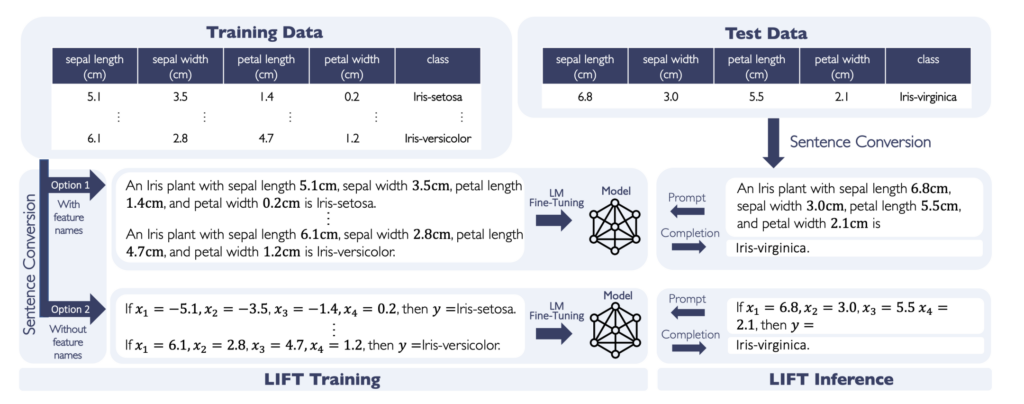

38. LIFT: Language-Interfaced Fine-Tuning for Non-Language Machine Learning Tasks

Tuan Dinh, Yuchen Zeng, Ruisu Zhang, Ziqian Lin, Michael Gira, Shashank Rajput, Jy-yong Sohn, Dimitris Papailiopoulos, Kangwook Lee. University of Wisconsin-Madison. NeurIPS 2022.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.06565

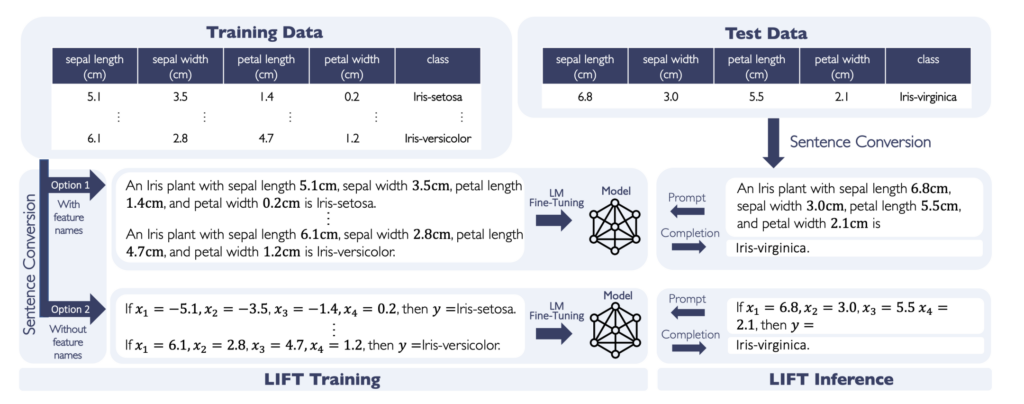

The paper investiagtes the application of pre-trained language models on the task of classifying non-textual data, without any architecture changes.

The input features are linearized into a text-like sequence and given as context, the output is then collected as a language model prediction.

While it doesn’g perform best overall, it does achieve surprisingly competitive performance.

39. Few-Shot Tabular Data Enrichment Using Fine-Tuned Transformer Architectures

Asaf Harari, Gilad Katz. Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. ACL 2022.

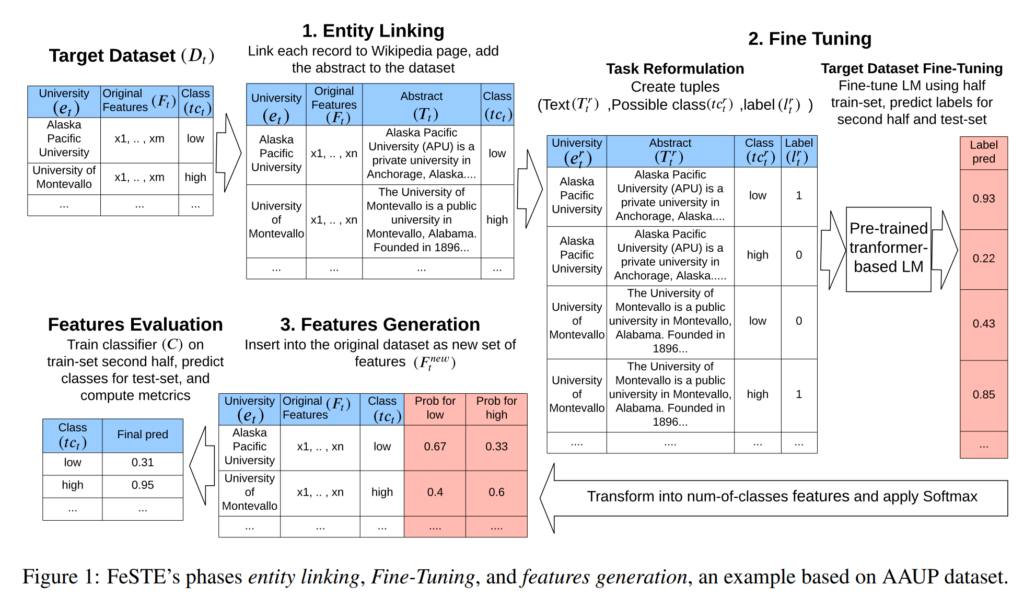

https://aclanthology.org/2022.acl-long.111.pdf

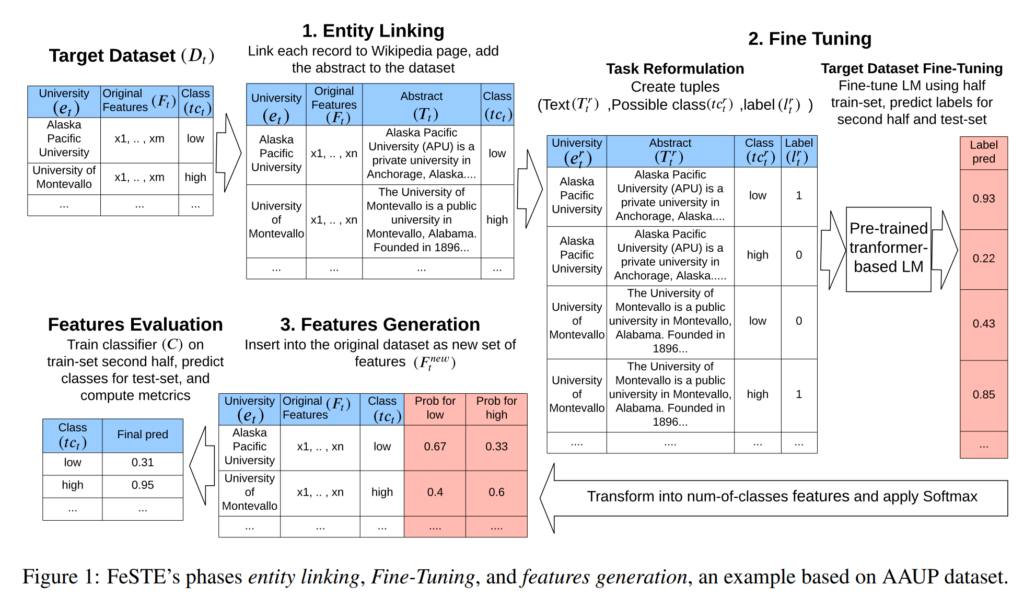

System for creating additional feature columns for a tabular dataset, which can then be useful for classification. Entities (rows) in the data are matched to wikipedia articles in order to retrieve plain text descriptions. Binary classifiers are then trained to classify this text according to properties from the tabular data, and the output probabilities are included as new features in the dataset. Evaluation is performed on the main classification task by using these new extra features.

40. Counterfactual Memorization in Neural Language Models

Chiyuan Zhang, Daphne Ippolito, Katherine Lee, Matthew Jagielski, Florian Tramèr, Nicholas Carlini. Google Research, Carnegie Mellon University, Google DeepMind, ETH Zürich. NeurIPS 2023.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.12938

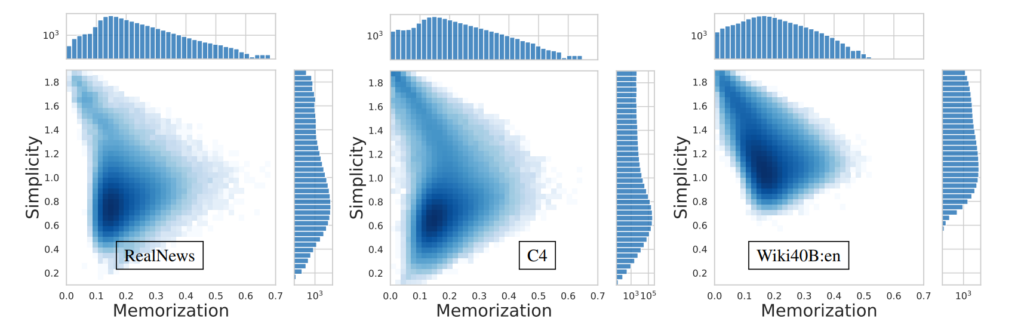

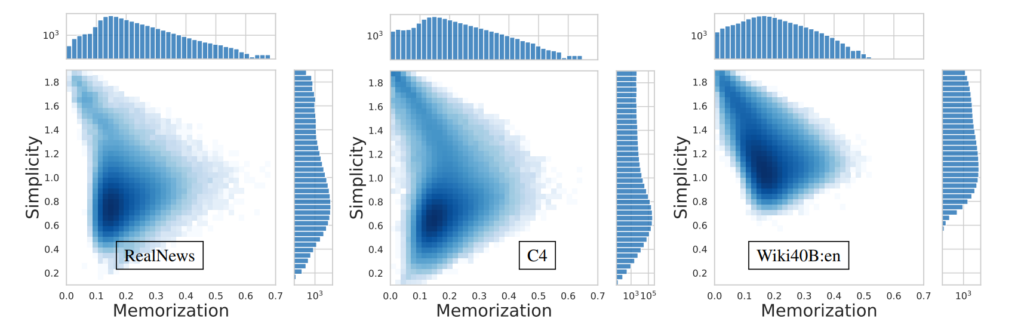

The paper proposes a measure of counterfactual memorization for pre-trained language models.

A large number of different models are trained on subsets of the training set.

The expected performance on that sentence is then calculated for examples containing a particular sentence, versus those that do not contain this sentence.

A high score difference indicates that the model tends to memorize this sentence when it is included in the training data.

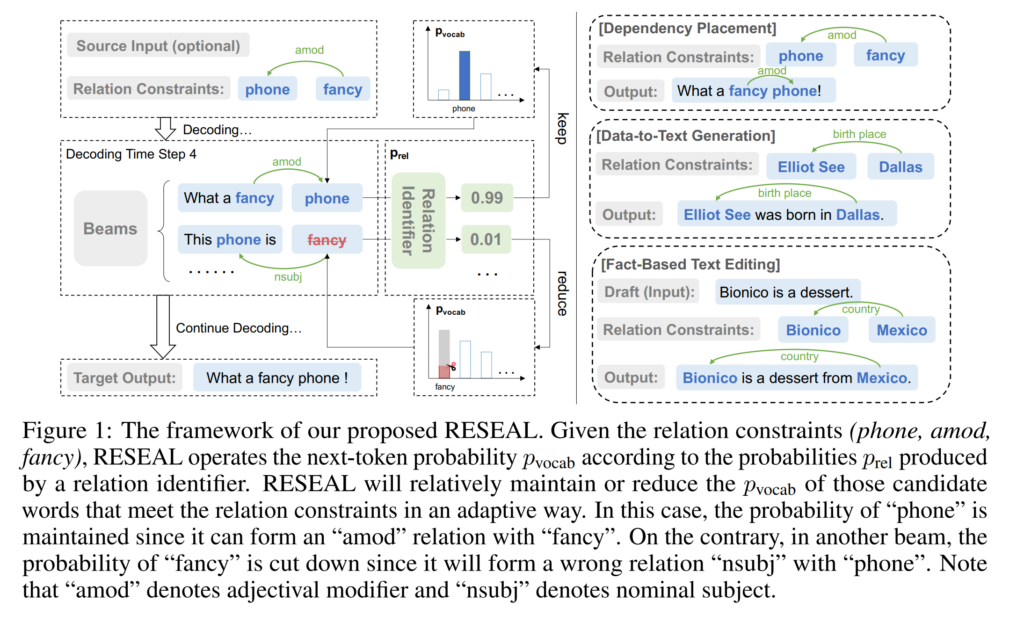

41. Relation-Constrained Decoding for Text Generation

Xiang Chen, Zhixian Yang, Xiaojun Wan. Peking University. NeurIPS 2022.

https://openreview.net/forum?id=dIUQ5haSOI

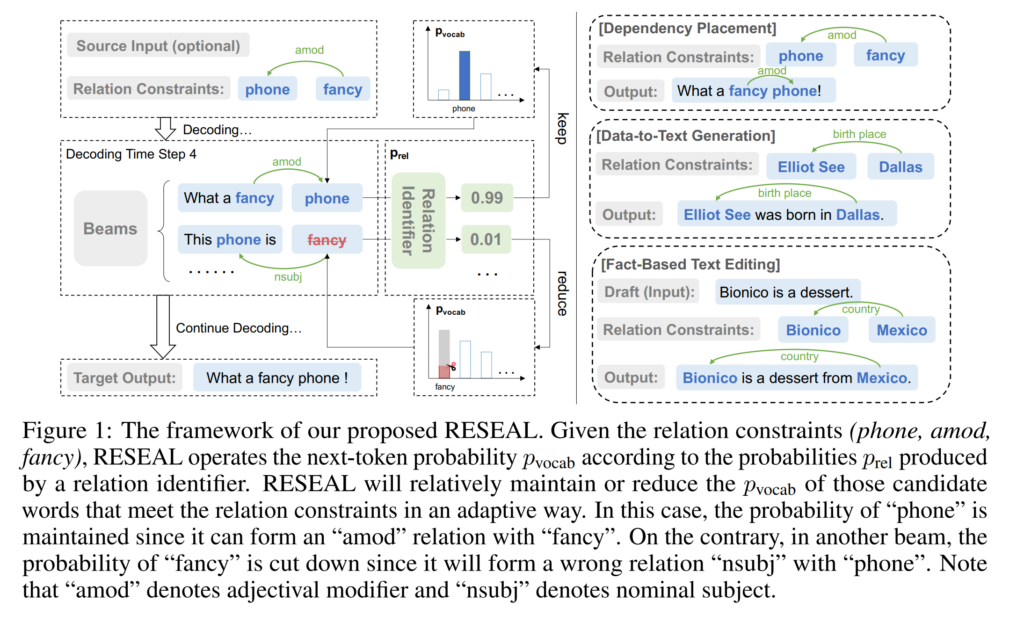

The paper describes a model for text generation, based on target dependency relations that should be in the output.

The word-level output probabilties are modified to increase the likelihood of generating words that match the target relation.

During beam decoding, the candidate construction method also takes the target relations into account.

Evaluation is performed on several datasets, formulating the task as text generation based on dependency relations.

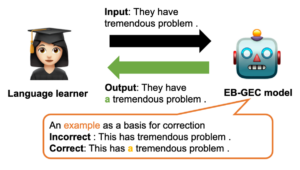

42. Interpretability for Language Learners Using Example-Based Grammatical Error Correction

Masahiro Kaneko, Sho Takase, Ayana Niwa, Naoaki Okazaki. Tokyo Institute of Technology. ACL 2022.

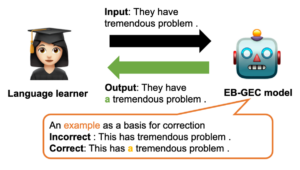

https://aclanthology.org/2022.acl-long.496

Describes a system for performing error correction, while also returning examples of similar corrections from the training set. Each token in each sentence is encoded with the GEC model and the representation is used for finding other similar correction examples. The kNN-based similarity is also incorporated into the output distribution of the error correction model, improving performance on closed-class errors while reducing some performance on open-class errors.

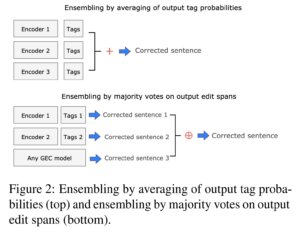

43. Ensembling and Knowledge Distilling of Large Sequence Taggers for Grammatical Error Correction

Maksym Tarnavskyi, Artem Chernodub, Kostiantyn Omelianchuk. Ukrainian Catholic University, Grammarly. ACL 2022.

https://aclanthology.org/2022.acl-long.266

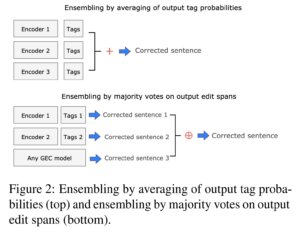

The paper extends the GECToR sequence tagging architecture for grammatical error correction.

The models are scaled up to bigger versions, multiple versions are ensembled together and then distilled back to a single model through generated training data. Improvements are shown on the BEA-2019 dataset both for the ensembled configuration and the single best model.

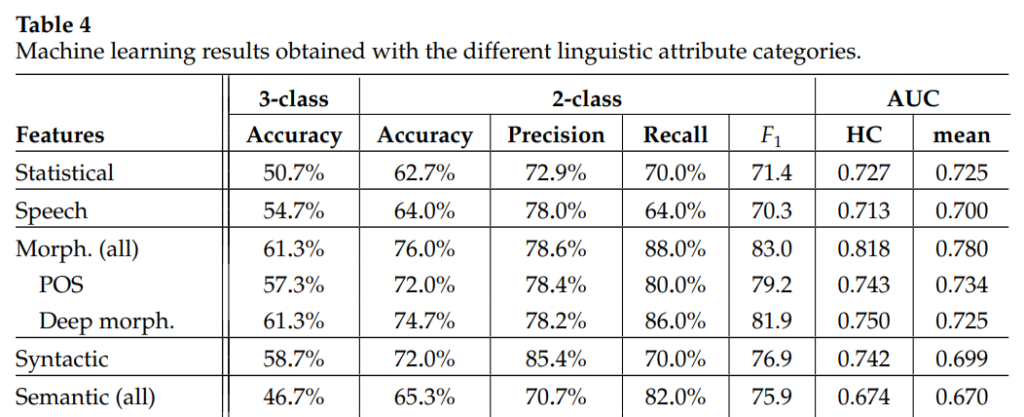

44. Linguistic Parameters of Spontaneous Speech for Identifying Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer Disease

Veronika Vincze, Martina Katalin Szabó, Ildikó Hoffmann, László Tóth, Magdolna Pákáski, János Kálmán, Gábor Gosztolya. University of Szeged. Computational Linguistics 2022.

https://aclanthology.org/2022.cl-1.5

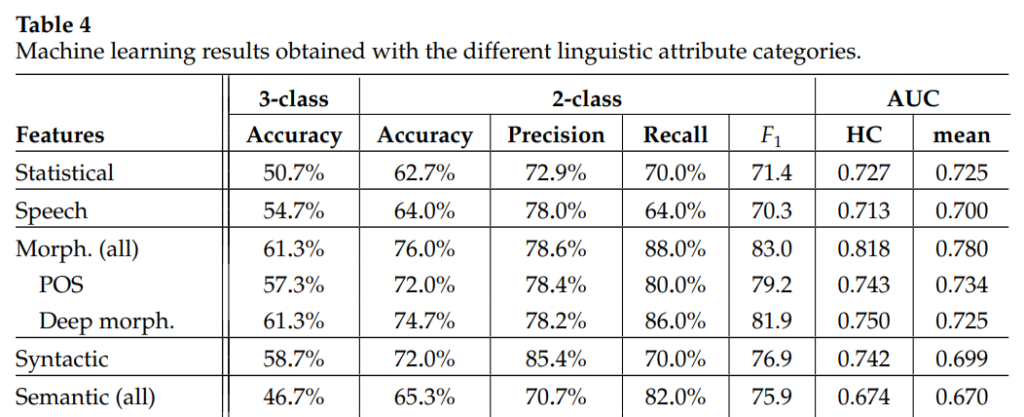

Developing a system for the detection of cognitive impairment based on linguistic features.

Patients were recorded when answering free-text questions, their answers transcribed, and a large number of features extracted for classification.

Morphological and statistical features perform well across different tasks and the overall classifier achieves 2-class F1 of 84-86%.

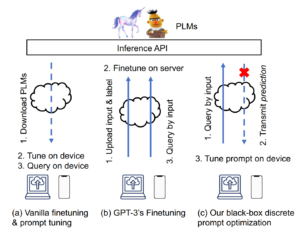

45. Black-box Prompt Learning for Pre-trained Language Models

Shizhe Diao, Zhichao Huang, Ruijia Xu, Xuechun Li, Yong Lin, Xiao Zhou, Tong Zhang. The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, University of California San Diego. TMLR 2023.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.08531

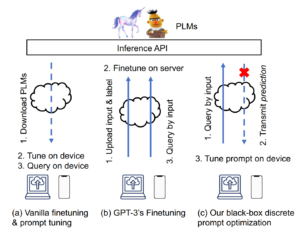

The paper proposes the task of tuning prompts for pre-trained models in a setting where the model weights or activations are not available and need to be treated as a black box.

A first stage of white-box fine-tuning using a small dataset is assumed, followed by a black-box tuning stage using additional data just for updating the prompts.

The prompts are updated by randomly sampling permutations to the existing prompts, then approximating the gradient using the natural evolution strategy (NAS) algorithm.

Evaluation shows that having the extra black-box training step on additional data is beneficial over only doing white-box prompt tuning using a smaller dataset, but is outperformed by using the full dataset for white-box prompt tuning.

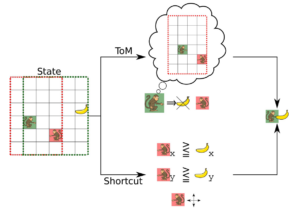

46. Mind the gap: Challenges of deep learning approaches to Theory of Mind

Jaan Aru, Aqeel Labash, Oriol Corcoll, Raul Vicente. University of Tartu. ArXiv 2022.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.16540

An opinion paper on deep learning models in connection to the Theory of Mind – the skill of humans to understand the minds of others, imagine that they might have hidden knowledge or emotions. Gives a summary of different stages of this skill developing in humans, along with a review of this work in the deep learning field. Proposes that this is not a skill that will develop from one task, and that it should be evaluated through the interpretation of neural networks (for example whether a specific neuron can be identified to detect the emotion of others).

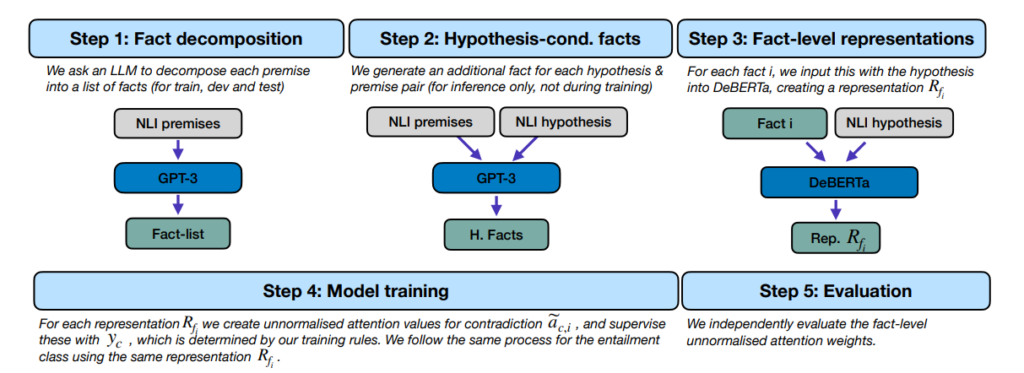

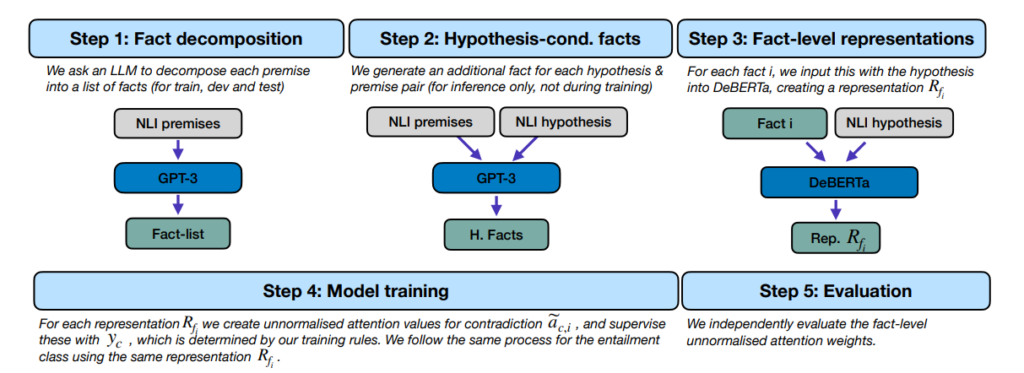

47. Atomic Inference for NLI with Generated Facts as Atoms

Joe Stacey, Pasquale Minervini, Haim Dubossarsky, Oana-Maria Camburu, Marek Rei. Imperial, Edinburgh, QMUL, UCL. EMNLP 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.13214

Long texts are broken down into individual self-contained facts using an LLM. A special architecture then learns to make decisions about the text by making individual entailment decisions about those facts. The resulting system is able to point to specific facts as explanations for the overall decision, as these are guaranteed to be a faithful explanation for the final prediction.

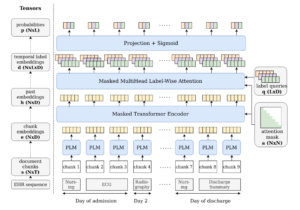

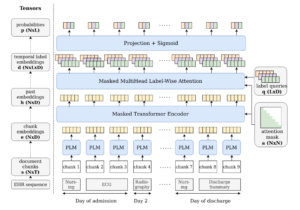

48. Continuous Predictive Modeling of Clinical Notes and ICD Codes in Patient Health Records

Mireia Hernandez Caralt, Clarence Boon Liang Ng, Marek Rei. Imperial. BioNLP 2024.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2405.11622

Investigates the task of early prediction of hospital diagnoses and necessary procedures, based on textual notes in the electronic health records. A causal hierarchical model is created, which is able to make predictions about overall ICD codes at every timestep of the hospital stay. As the note sequences are very long, an extended context algorithm is proposed, which samples a subset of notes during training but is able to iteratively use the whole sequence during testing.

49. Modelling Temporal Document Sequences for Clinical ICD Coding

Clarence Boon Liang Ng, Diogo Santos, Marek Rei. Imperial, Transformative AI. EACL 2023.

https://aclanthology.org/2023.eacl-main.120.pdf

Assigning ICD codes to discharge summaries in electronic health records, which indicate the diagnoses and procedures for each patient. The model is designed to integrate additional information from the previous notes in the health record. Additive embeddings are used for representing metadata about each note. The system achieves state-of-the-art results on the task of ICD coding.

50. When and Why Does Bias Mitigation Work ?

Abhilasha Ravichander, Joe Stacey, Marek Rei. Ai2, Imperial. EMNLP 2023.

https://aclanthology.org/2023.findings-emnlp.619

Targeted testing of different model debiasing methods, in order to investigate their effect on the model. Creating six datasets that contain very specific controlled biases for probing debiasing methods. Experiments show that specifically debiasing against one bias actually increases reliance against another bias.

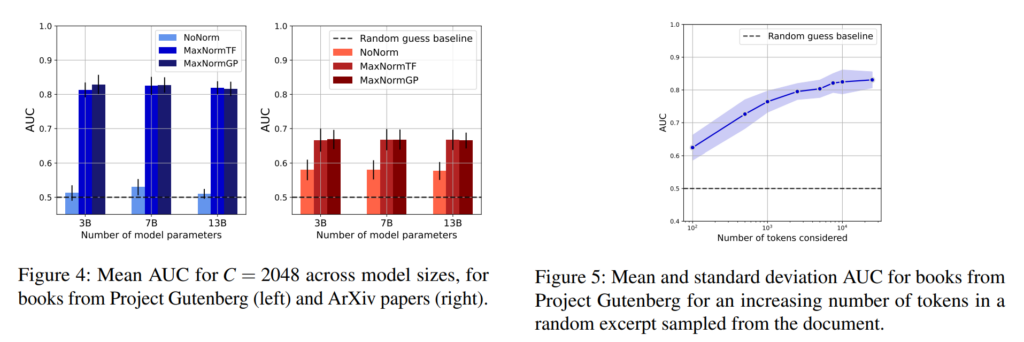

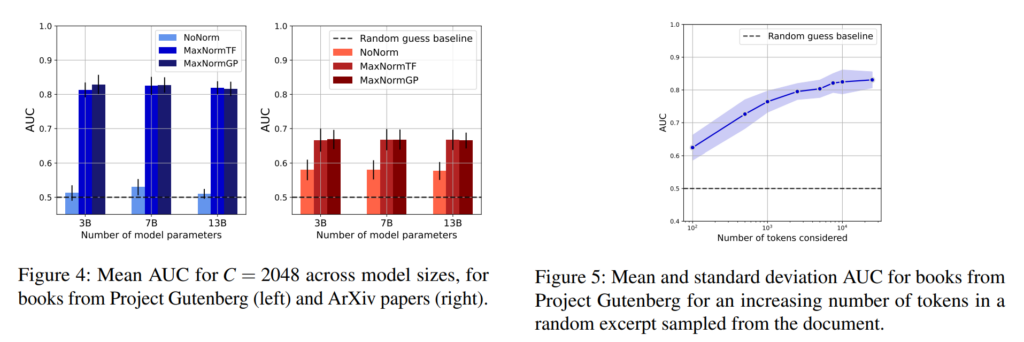

51. Did the Neurons Read your Book? Document-level Membership Inference for Large Language Models

Matthieu Meeus, Shubham Jain, Marek Rei, Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye. Imperial College London, Sense Street. USENIX Security Symposium 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.15007

Introducing the task of document-level membership inference for LLMs – determining whether a particular document (e.g. book or article) has been using during the LLM training, while only having query access to the resulting model. All token-level probabilities are collected from the language model, these are normalised by how rare each token is overall, and then aggregated into features and given to a supervised classifier. Experiments show that most documents can be detected, with the detection working better for longer documents.

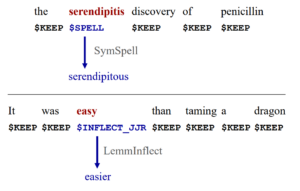

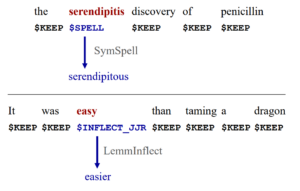

52. An Extended Sequence Tagging Vocabulary for Grammatical Error Correction

Stuart Mesham, Christopher Bryant, Marek Rei, Zheng Yuan. University of Cambridge, Imperial College London, King’s College London. EACL 2023.

https://aclanthology.org/2023.findings-eacl.119

Introducing tool usage into a tagging-based grammatical error correction model. Instead of training the model to correct every type of error itself, the model detects when a word should be sent to a separate spellcheck or an inflection system. The modification improves performance on the targeted error types and overall, also leaving room for introducing additional tools for other error types.

53. On the application of Large Language Models for language teaching and assessment technology

Andrew Caines, Luca Benedetto, Shiva Taslimipoor, Christopher Davis, Yuan Gao, Oeistein Andersen, Zheng Yuan, Mark Elliott, Russell Moore, Christopher Bryant, Marek Rei, Helen Yannakoudakis, Andrew Mullooly, Diane Nicholls, Paula Buttery. Cambridge, KCL, CUPA, Writer Inc, Imperial, ELiT. AIED LLM 2023.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.08393

Discussing the possible applications of generative language models in the area of language teaching. Covering tasks such as automated test creation, question difficulty estimation, automated essay scoring and feedback generation. The paper concludes that there is a lot of potential but for best results the automated systems need to be paired with human intervention.

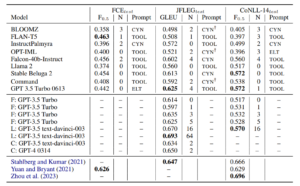

54. Prompting open-source and commercial language models for grammatical error correction of English learner text

Christopher Davis, Andrew Caines, Øistein Andersen, Shiva Taslimipoor, Helen Yannakoudakis, Zheng Yuan, Christopher Bryant, Marek Rei, Paula Buttery. Cambridge, Writer Inc, KCL, Imperial. ACL 2024.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2401.07702

Investigating the abilities of LLMs to perform grammatical error correction. 7 open-source and 3 commercial models are evaluated with 11 different prompts on established error correction benchmarks. LLMs perform the best on fluency edits but do not come close to state-of-the-art performance on minimal corrections of grammatical errors.

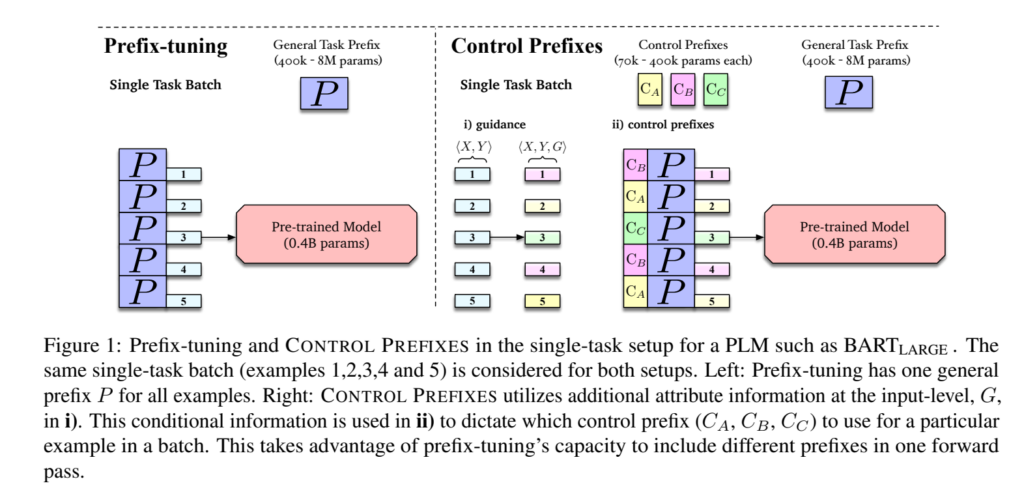

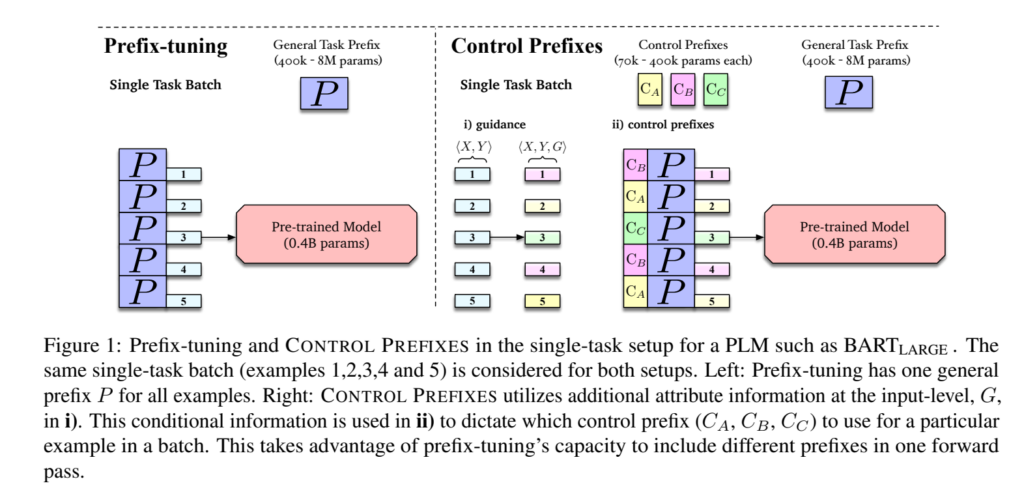

55. Control Prefixes for Parameter-Efficient Text Generation

Jordan Clive, Kris Cao, Marek Rei. Imperial, DeepMind, Cambridge. GEM 2022.

https://aclanthology.org/2022.gem-1.31

Introducing control prefixes, which are plug-and-play modules for influencing text generation into a particular direction. By switching on a particular control prefix, the model can generate text in a particular domain, in a particular style or at a specific length. Experiments also include predicting values for a previously unseen generation category.

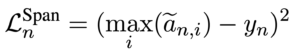

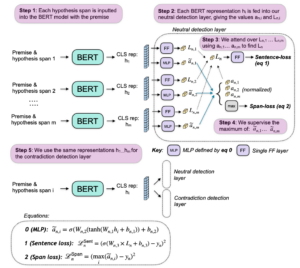

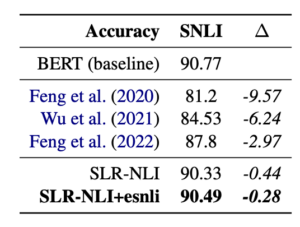

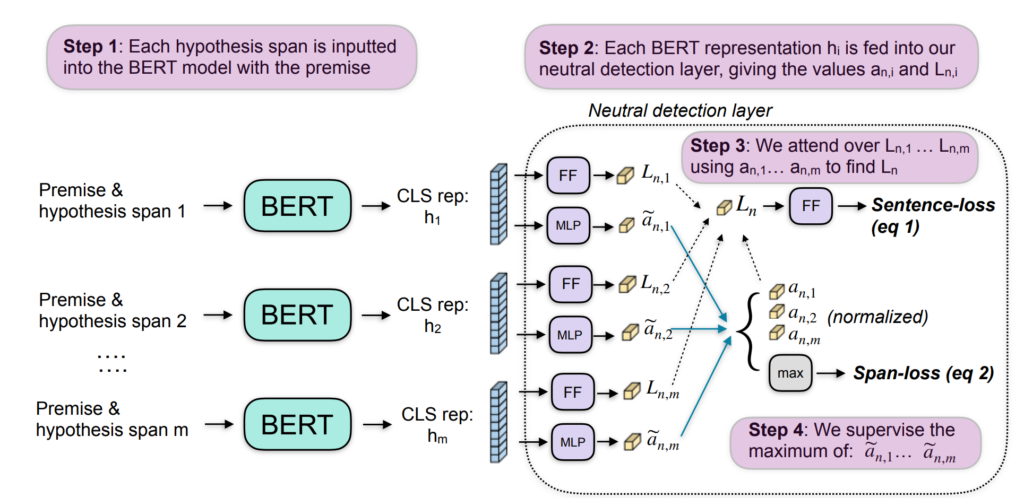

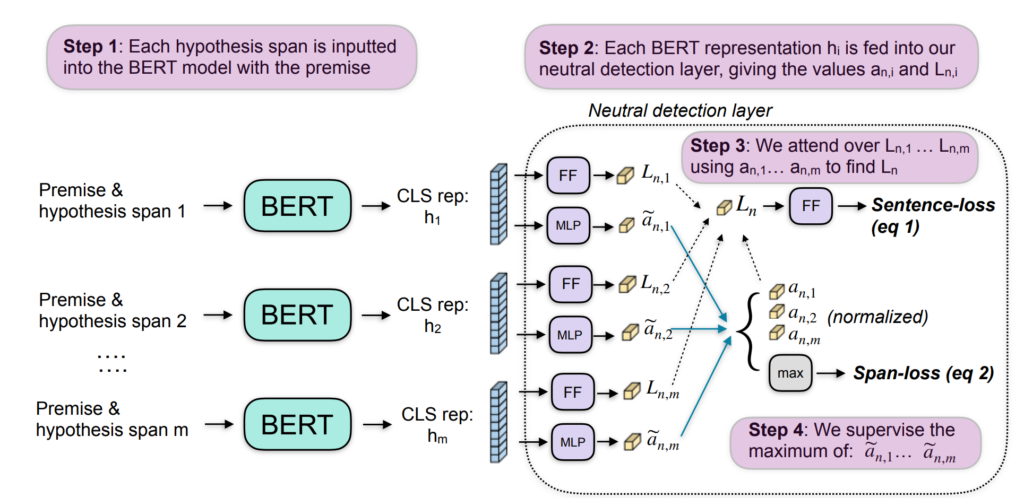

56. Logical Reasoning with Span-Level Predictions for Interpretable and Robust NLI Models

Joe Stacey, Pasquale Minervini, Haim Dubossarsky, Marek Rei. Imperial College London, University of Edinburgh, UCL, Queen Mary University of London. EMNLP 2022.

https://aclanthology.org/2022.emnlp-main.251

A neural architecture for entailment detection (NLI) that has guarantees on the faithfulness of its explanations. Text is broken into shorter spans, the model makes predictions about each span separately and the final overall decision is found deterministically based on the span-level predictions. The updated model retains performance while being more explainable, and also outperforms all previous logical architectures for entailment detection.

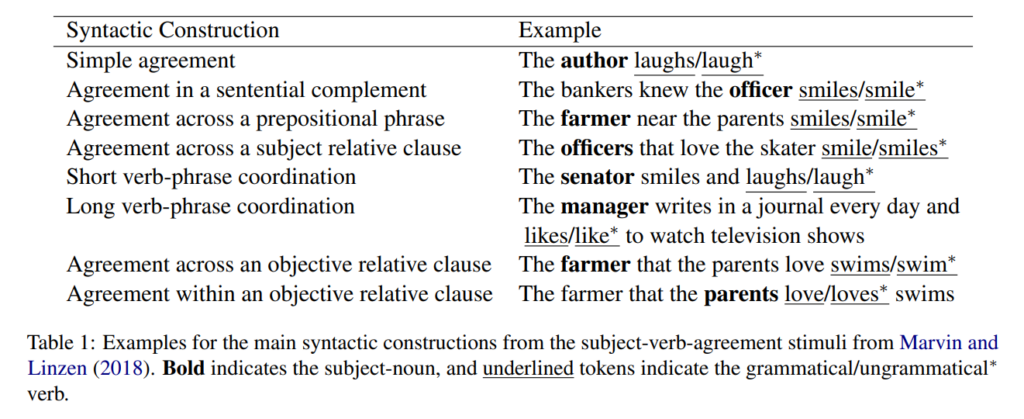

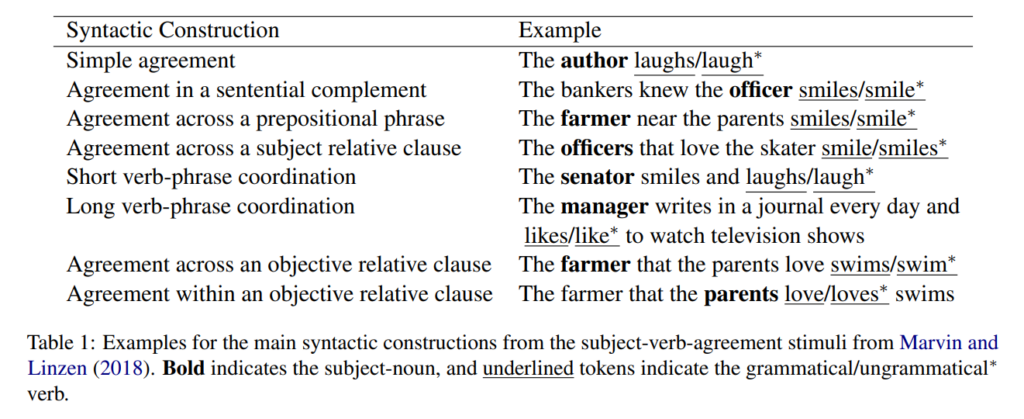

57. Probing for targeted syntactic knowledge through grammatical error detection

Christopher Davis, Christopher Bryant, Andrew Caines, Marek Rei, Paula Buttery. Cambridge, Imperial. CoNLL 2022.

https://aclanthology.org/2022.conll-1.25

Investigating how much pre-trained language models capture syntactic information and how well are they able to detect syntactic errors out-of-the-box. Different language models are frozen and small probes are trained on top of them to identify specific errors in text. Analysis shows that the final layers of ELECTRA and BERT capture subject-verb agreement errors best.

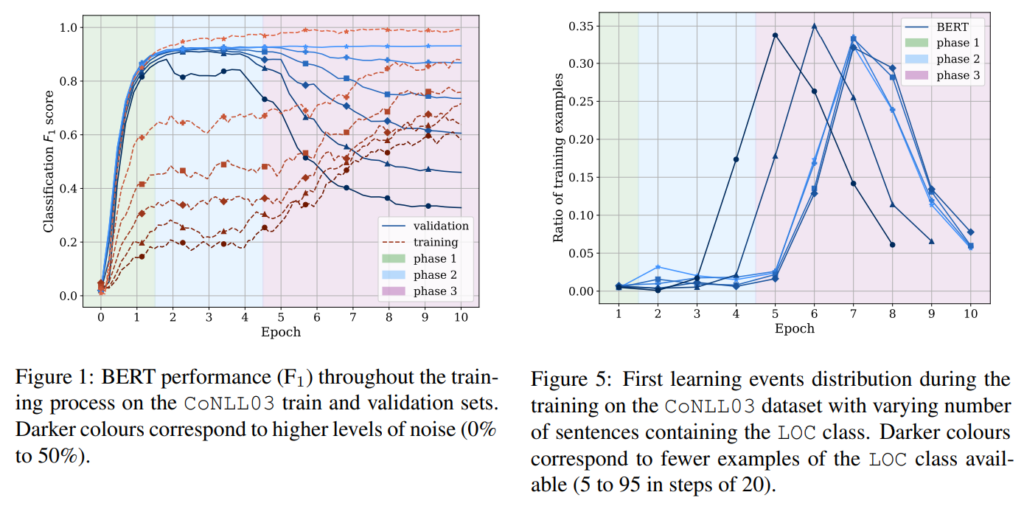

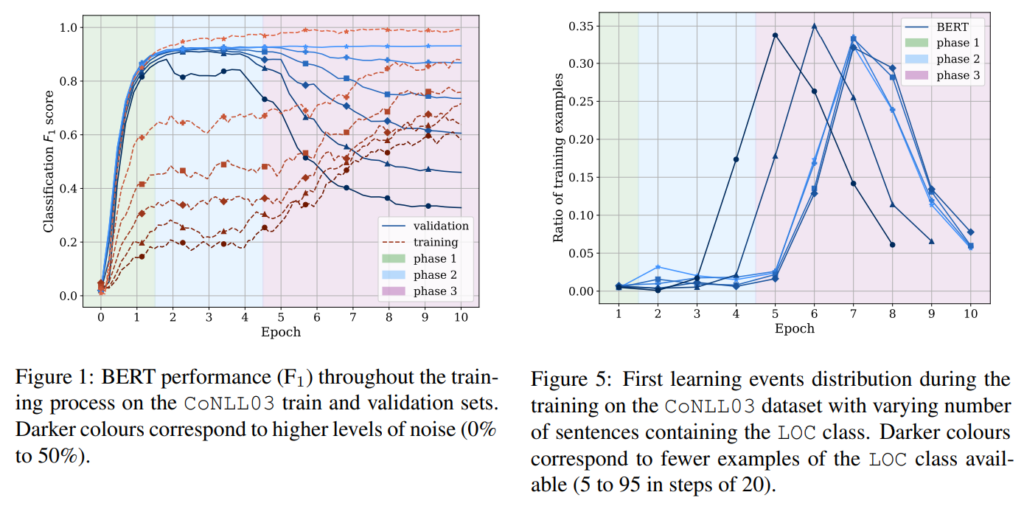

58. Memorisation versus Generalisation in Pre-trained Language Models

Michael Tänzer, Sebastian Ruder, Marek Rei. Imperial, Google Research. ACL 2022.

https://aclanthology.org/2022.acl-long.521

Investigating the learning abilities of language models under controlled experiments. Results show that LMs are surprisingly resilient to noise in the training data, with the resulting performance being nearly unaffected as long as the learning is stopped at an optimal time. However, the models are not able to differentiate between label noise and low-resource classes, with overall performance deteriorating just as the rare classes start to be learned. The paper proposes a model based on class prototypes to get the best of both worlds.

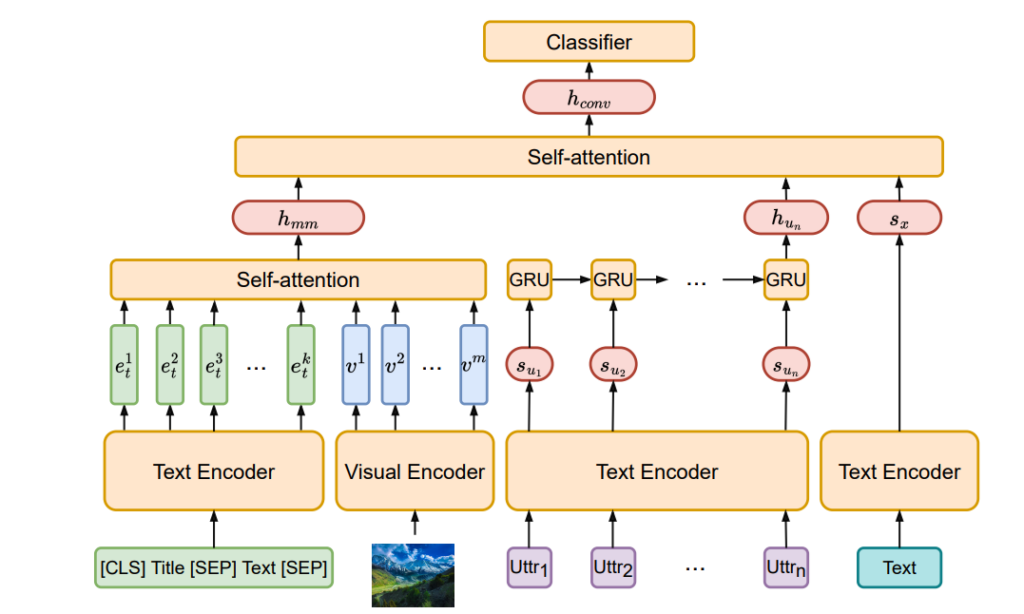

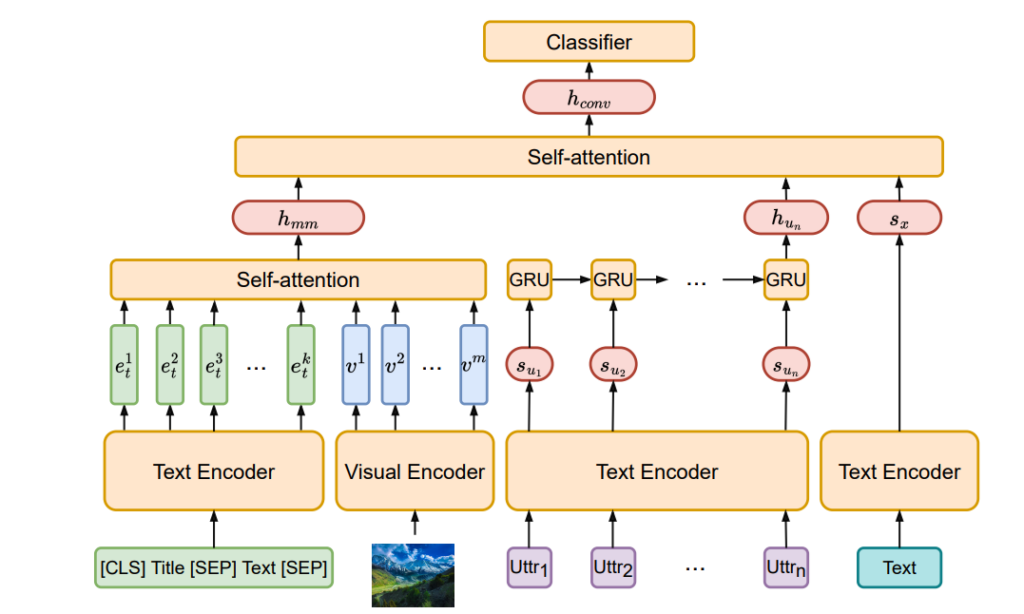

59. Multimodal Conversation Modelling for Topic Derailment Detection

Zhenhao Li, Marek Rei, Lucia Specia. Imperial. EMNLP 2022.

https://aclanthology.org/2022.findings-emnlp.376

Creating and releasing a dataset of reddit threads that contain images. Posts that derail the conversation are then identified and annotated with the derailment type, such as starting a new topic, spamming or making toxic comments. A multimodal architecture for this task is also described, which encodes the post, the image and the context in order to make accurate decisions.

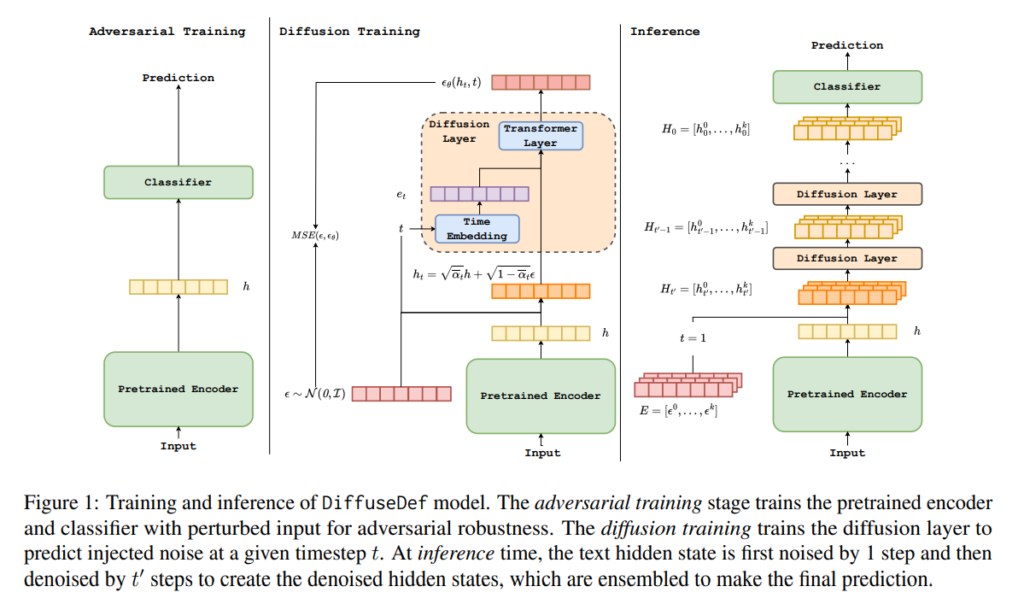

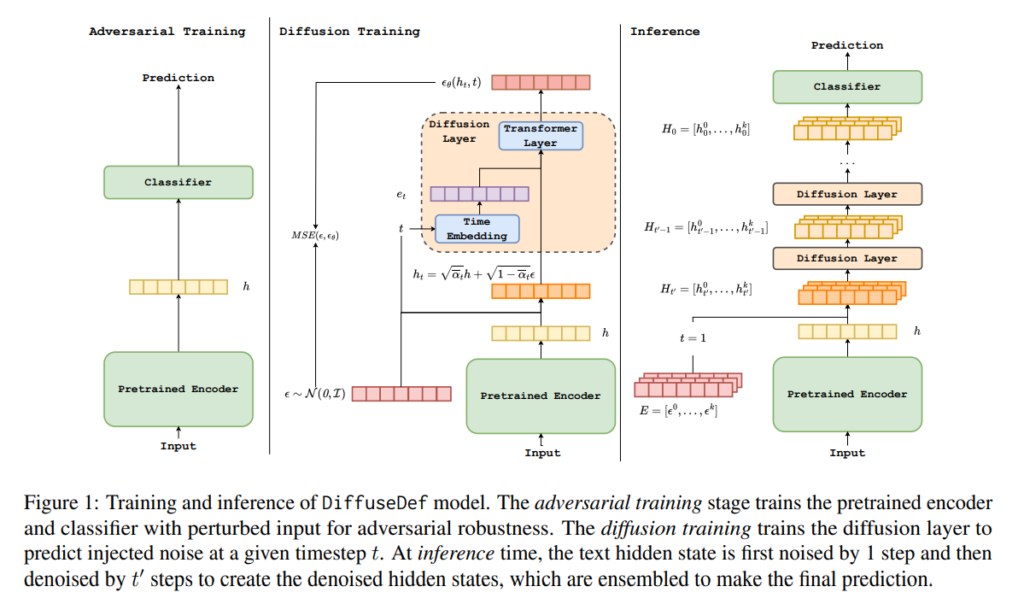

60. DiffuseDef: Improved Robustness to Adversarial Attacks

Zhenhao Li, Marek Rei, Lucia Specia. Imperial. ArXiv.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.00248

Introducing a defusion module as a denoising step for text representations in order to prevent adversarial attacks.

The diffusion layer is trained on top of a frozen encoder to predict the randomly inserted noise in the representation.

During inference, this noise is then subtracted over multiple iterations to get a clean representation.

Results show state-of-the-art results for resisting adversarial attacks.

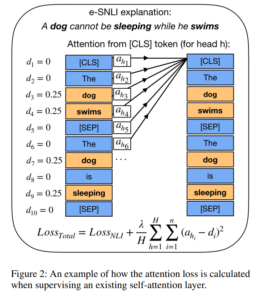

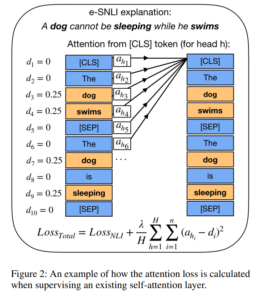

61. Supervising Model Attention with Human Explanations for Robust Natural Language Inference

Joe Stacey, Yonatan Belinkov, Marek Rei. Imperial, Technion. AAAI 2022.

https://cdn.aaai.org/ojs/21386/21386-13-25399-1-2-20220628.pdf

Investigating how natural language explanations of particular label assignments can be used to improve model performance.

The method identifies important words in the input, either based on explanation text or highlights, and then trains the model to assign higher self-attention weights to those tokens. Experiments show that this method consistently improves performance, making the model focus more on the relevant evidence.

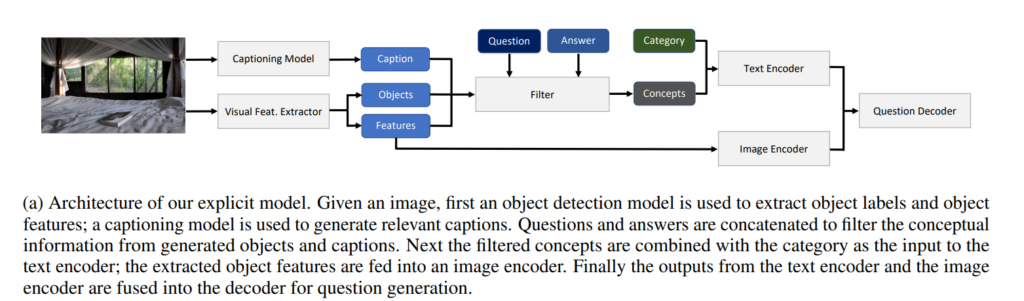

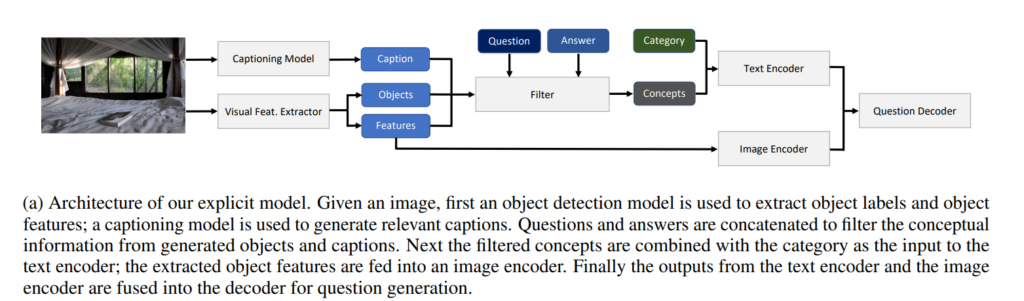

62. Guiding Visual Question Generation

Nihir Vedd, Zixu Wang, Marek Rei, Yishu Miao, Lucia Specia. Imperial. NAACL 2022.

https://aclanthology.org/2022.naacl-main.118.pdf

Investigates guiding the process of visual question generation, where the system generates questions about a given image.

The architecture allows the user to specify categories or objects in the image, which the system will then ask about.

These choices can also be modeled as latent variables inside the model, leading to state-of-the-art results in regular VQG.

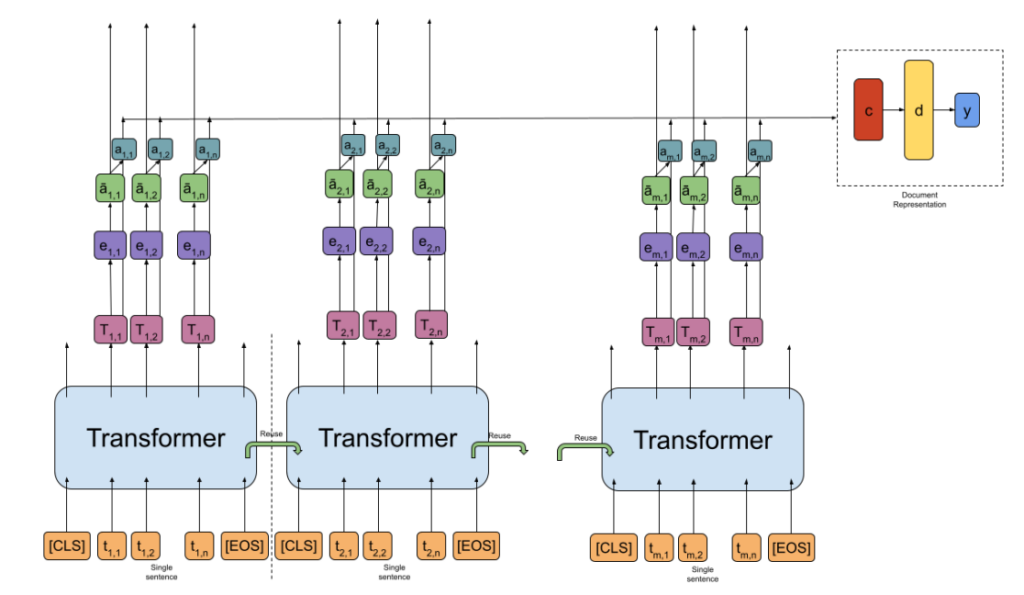

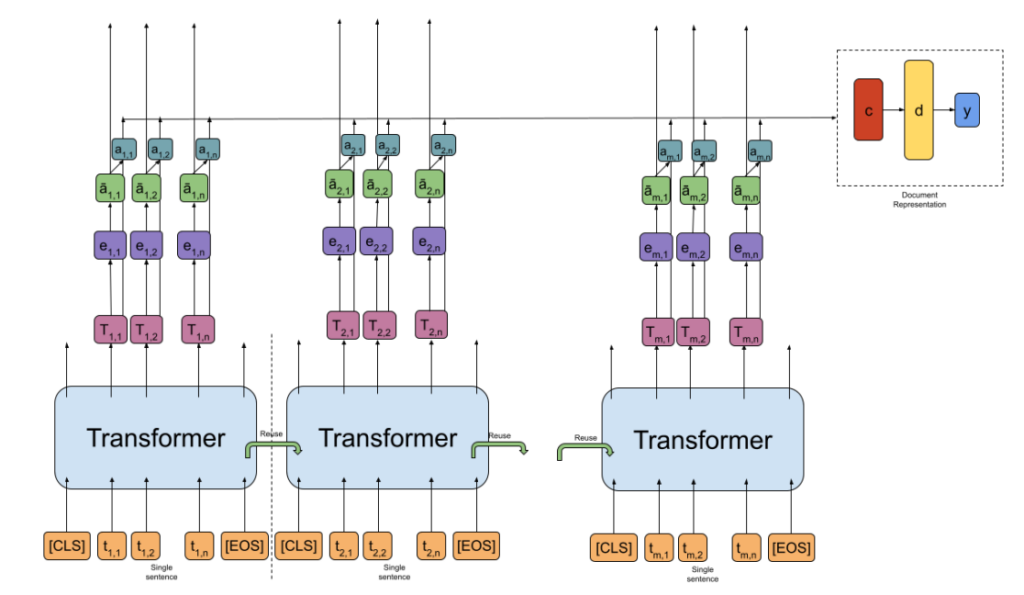

63. Finding the Needle in a Haystack: Unsupervised Rationale Extraction from Long Text Classifiers

Kamil Bujel, Andrew Caines, Helen Yannakoudakis, Marek Rei. Imperial, Cambridge, KCL. Arxiv 2023.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2303.07991

Designing a hierarchical transformer model that is able to explain itself by pointing to relevant tokens in the input.

It indirectly supervises the attention on a certain number of tokens at each turn, in order to make the model behave like a binary importance classifier on the token level. Previous methods that work well on shorter texts (e.g. individual sentences) are shown to not work well when applied to longer texts.

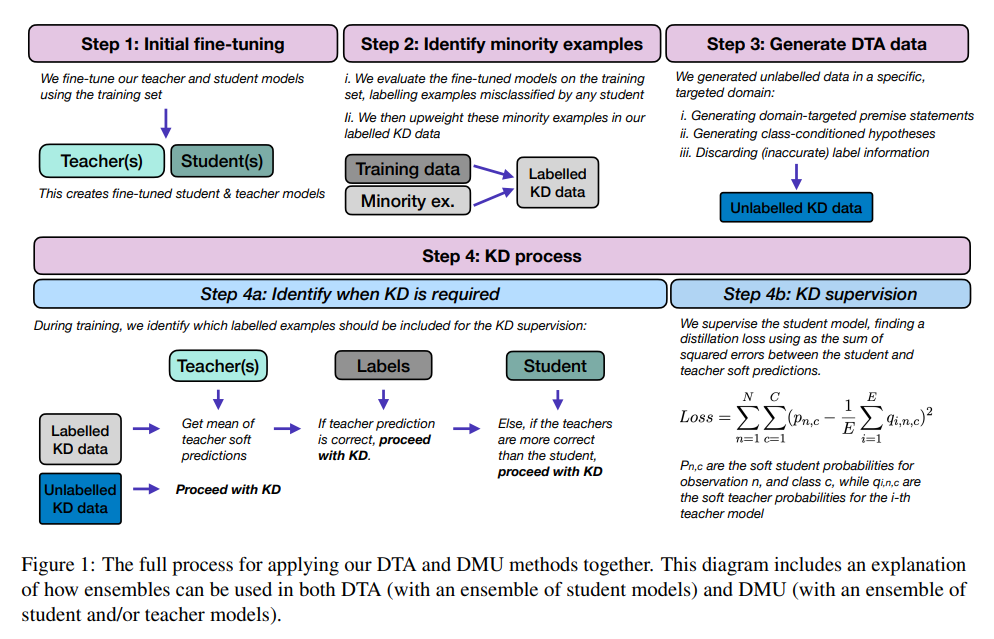

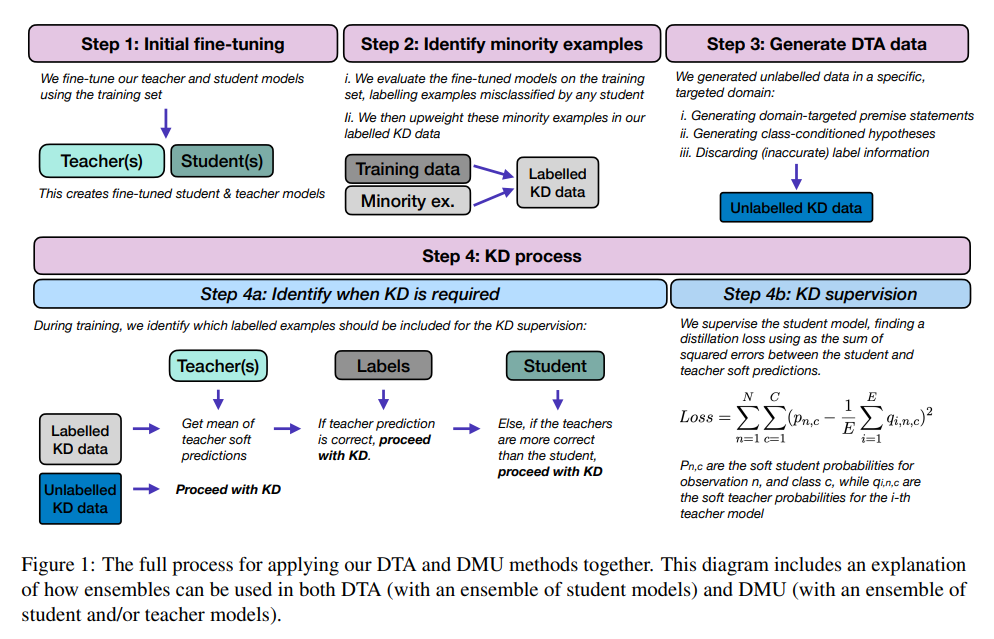

64. Distilling Robustness into Natural Language Inference Models with Domain-Targeted Augmentation

Joe Stacey, Marek Rei. Imperial. ACL 2024.

https://aclanthology.org/2024.findings-acl.132.pdf

Investigating model distillation methods that would be better able to generalise to previously unseen domains. The methods either generate new unlabeled examples or upweight existing examples from the training data that are more similar to a particular domain, then use these as input during the distilling process. Experiments show that this increases robustness also towards domains which are not considered during distillation.

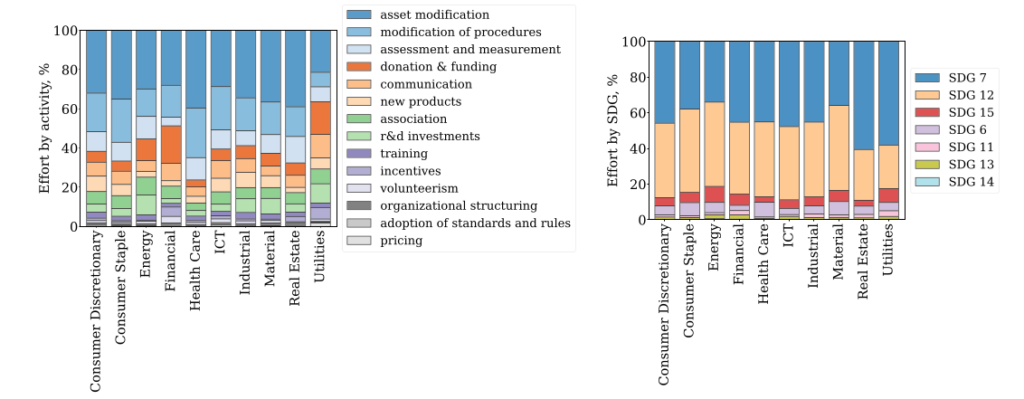

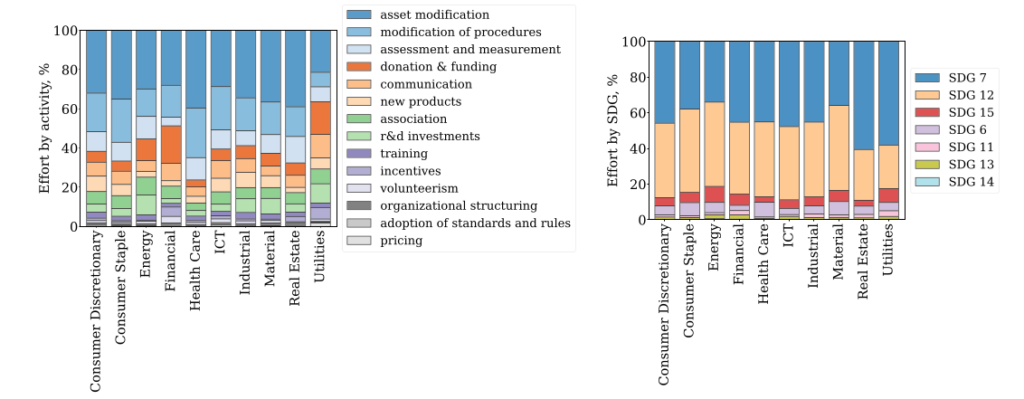

65. The alignment of companies’ sustainability behavior and emissions with global climate targets

Simone Cenci, Matteo Burato, Marek Rei, Maurizio Zollo. Imperial. Nature Communications 2024.

Applying NLP systems to analyse thousands of company reports and the sustainability initiatives described in those reports.

The system crawls public reports online, extracts sentences that refer to sustainability initiatives implemented by that company, and classifies them based on type, stakeholder and one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals established by the UN.

Analysis indicates that companies are mostly investing in risk-prevention initiatives, as opposed to innovation and cooperation.

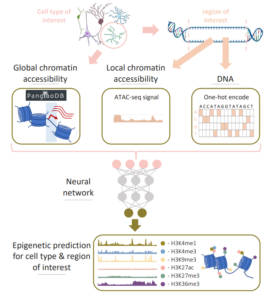

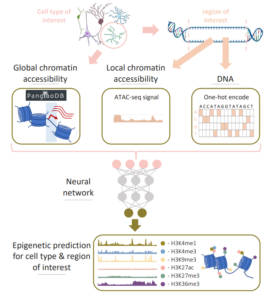

66. Predicting cell type-specific epigenomic profiles accounting for distal genetic effects

Alan E Murphy, William Beardall, Marek Rei, Mike Phuycharoen, Nathan G Skene. Imperial, Manchester. Nature Communications 2024.

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.02.15.580484

Using architectures based on pre-trained transformer language models and extending them for the domain of genome modeling.

Proposing and releasing Enformer Celltyping, which can incorporate long-range context of DNA base pairs and predict epigenetic signals while being cell type-agnostic.

67. SoK: Membership Inference Attacks on LLMs are Rushing Nowhere (and How to Fix It)

Matthieu Meeus, Igor Shilov, Shubham Jain, Manuel Faysse, Marek Rei, Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye. Imperial, Sense Street, Université Paris-Saclay. Arxiv 2024.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2406.17975

In order to develop methods for detecting whether specific copyrighted work has been used for training a particular LLM, researchers have collected datasets of known documents that are (or are not) part of specific training sets. However, these datasets are normally collected post-hoc, leading to distibution differences. The experiments show that many detection models misleadingly react to those differences, instead of truly detecting the documents in the training data. Suggestions are provided for preventing this issue in future experiments.

68. StateAct: State Tracking and Reasoning for Acting and Planning with Large Language Models

Nikolai Rozanov, Marek Rei. Imperial. Arxiv 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.02810

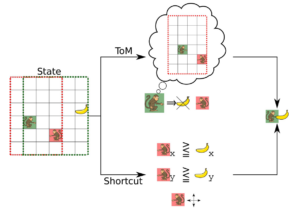

Improving LLMs for long-range planning and reasoning, for tasks which require a large number of steps to complete.

As the length of the few-shot examples and the generated trace grows longer, LLMs can lose track of what they are supposed to do and what they have done already. Periodically reminding them of the task and explicitly keeping track of their state provides consistent improvements in performance, establishing a new state-of-the-art result for the Alfworld benchmark.